2025 Infrastructure Market Capacity Report

13 November 2025

Chief Commissioner’s foreword

Each year, Infrastructure Australia evaluates the demand to build across the nation, and calculates the resources required to deliver on that demand. Now in its fifth year, this research offers an evidence base to strengthen national coordination, ensuring that infrastructure investment is both achievable and sustainable.

The research helps governments better sequence their project pipelines by providing a clearer view of the workforce and materials needed. It offers a national perspective, enabling jurisdictions to focus beyond borders on construction market issues across the country.

We have ambitious goals ahead of us — lifting national productivity, transitioning to a clean energy future, and substantially boosting housing supply to meet the needs of Australians today and into the future. Infrastructure is a critical enabler of economic growth and social outcomes. A cross-jurisdictional, cross-sector view of the pipeline helps us make better decisions on what to build, when to build it, and how to meet the needs of communities.

The research has drawn international attention, with jurisdictions like Canada pursuing similar work to support their ambitious housing programs whilst facing workforce shortages and productivity challenges.

The strength of this research lies in the collaborative relationships Infrastructure Australia has formed across industry and government and with our international counterparts. We acknowledge and thank all participants for the part they played in developing this year’s report, through data sharing and close collaboration.

Our Infrastructure Market Capacity research has grown into a trusted and reliable source of information that captures the $1.14 trillion of construction activity happening right across the country. The report also continues to detail and explore the plant, labour, equipment and materials needed to deliver on the nation’s five-year Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline —which has grown 14% over the last year and now stands at $242 billion.

The successful planning and delivery of infrastructure is critical in supporting our nation’s growing cities and regions, particularly as we navigate the growth in investment across renewable energy and social infrastructure projects, while continuing to deliver record levels of investment in major transport projects.

As governments navigate these decisions, Infrastructure Australia is committed to supporting the Australian Government with independent advice to drive a thriving, efficient and productive construction sector for the economic and social prosperity of all Australians.

Tim Reardon

Executive summary

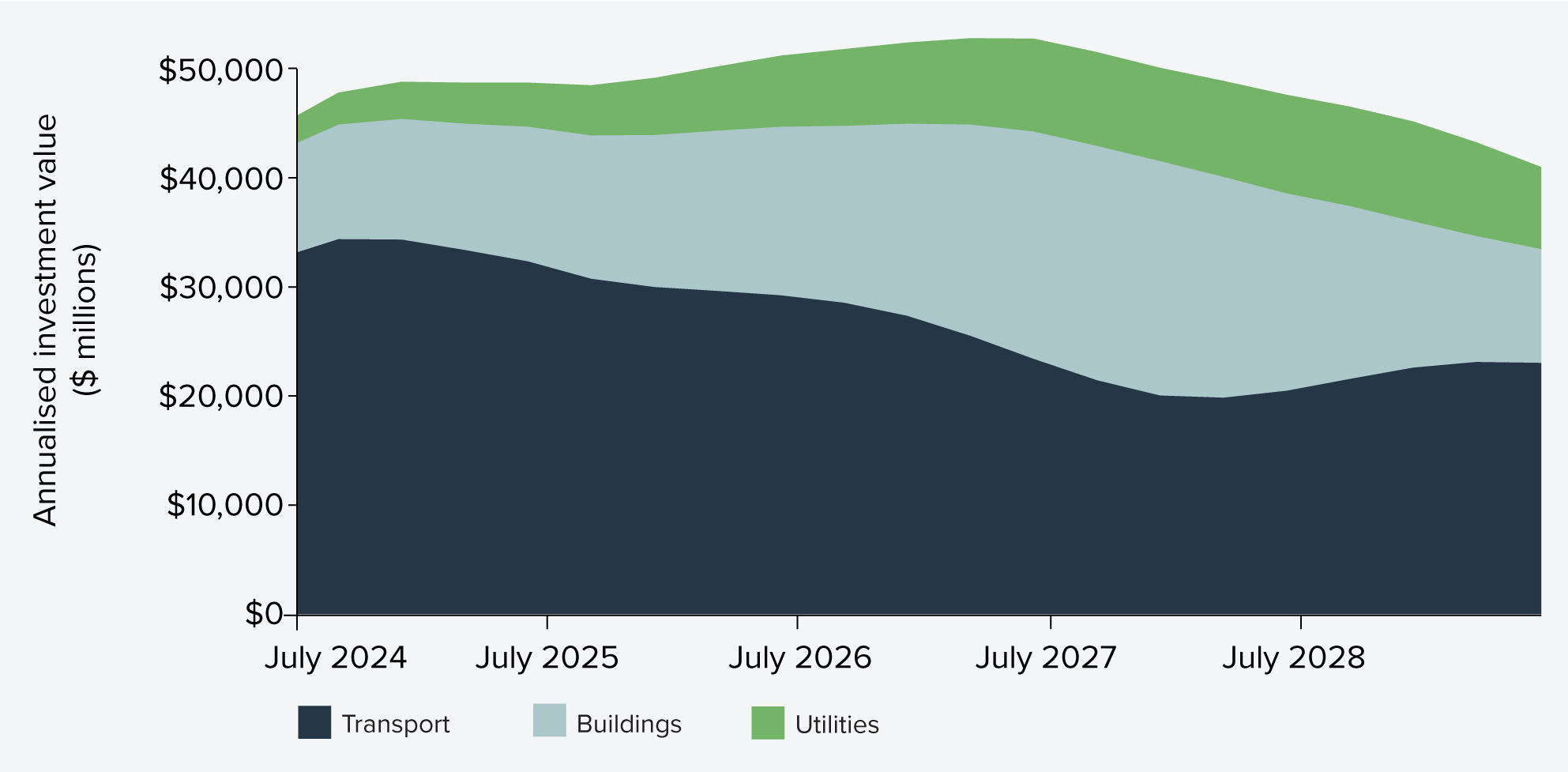

Australia’s Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline is $242 billion across the five years from financial years 2024–25 to 2028–29 (‘five-year outlook’), up 14% compared with the projection of 12 months earlier for the corresponding outlook period 2023–24 to 2027–28. This outcome reflects governments’ ambitions to boost housing stock and transition our energy sources towards a net zero future, while holding steady the record levels of investment in productivity-enhancing transport infrastructure.

Demand for major public infrastructure projects has risen for the first time since 2022 as governments grow investments in buildings and utilities while transport investment continues to dominate pipelines

Infrastructure Australia has updated its Market Capacity database with relevant Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline information provided by state and territory governments. A comparative analysis of the national Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline outlook versus the previous outlook period from 12 months earlier reveals:

- Demand has increased by 14% on the previous year’s outlook.

- There is a significant increase in either public-funded housing investments or energy transmission projects across all of Australia’s states and territories.

- Delivery challenges are slowing the rate of the energy transition, with delays to the start of construction for many private infrastructure energy projects.

Key changes in the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline across the past 12 months include:

- Transport infrastructure investment is projected at $129 billion and remains the largest expenditure category, accounting for 53% of the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline. This is a $3 billion (2%) increase on the previous year’s outlook and quite steady.

- Projected demand expected in the final year in the outlook period is much higher than observed in the first four editions of the Infrastructure Market Capacity reports. It indicates that government investment may be becoming more certain across a longer-term time horizon.

- Buildings infrastructure investment is projected at $77 billion, which accounts for 32% of the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline. This is up $6 billion on the previous year’s outlook (up $14 billion compared with the outlook from two years earlier). Buildings infrastructure is driven by social and affordable housing ($28 billion) and health projects ($22 billion).

- Utilities infrastructure investment is projected at $36 billion, which now accounts for 15% of the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline and is up $20 billion on the previous year’s outlook. This increase is predominantly explained by additional transmission line projects.

Materials cost escalations have stabilised, but more attention is needed to ensure sovereign capability in steel and increase uptake of low emissions materials

Cost growth of key materials such as cement and timber has eased to around inflation levels indicating stabilisation of price volatility seen during the Covid-19 years. Steel prices however continue to fall, a downward trend since 2022.

Domestic steel fabrication capability presents a potential sovereign supply chain risk to a key infrastructure input. The industry reports being under severe pressure from cheaper imports (offered at up to 50% cheaper than what local producers can viably offer) and with import volumes growing by 50%.

The Australian Government has committed to supporting green metals fabrication under the Future Made in Australia agenda (Green Metals Package), and to supporting the administration and sale of the Whyalla Steelworks, which produces 75% of Australia’s structural steel and is the only domestic source of long steel products.

More could be done now to ensure the sustainability of fabricators further down the steel supply chain.

At the same time, lower emissions and recycled materials remain a largely untapped pathway to reduce emissions in infrastructure delivery. A range of state and territory policies encourage the use of low-emission and recycled materials in infrastructure construction. This creates a strategic opportunity for governments to lead a nationally-coordinated approach that strengthens market capacity and accelerates industry growth.

Stronger procurement levers, harmonised standards, and pathways beyond research and pilots are needed to scale adoption and fully realise the decarbonisation potential on an industrial scale.

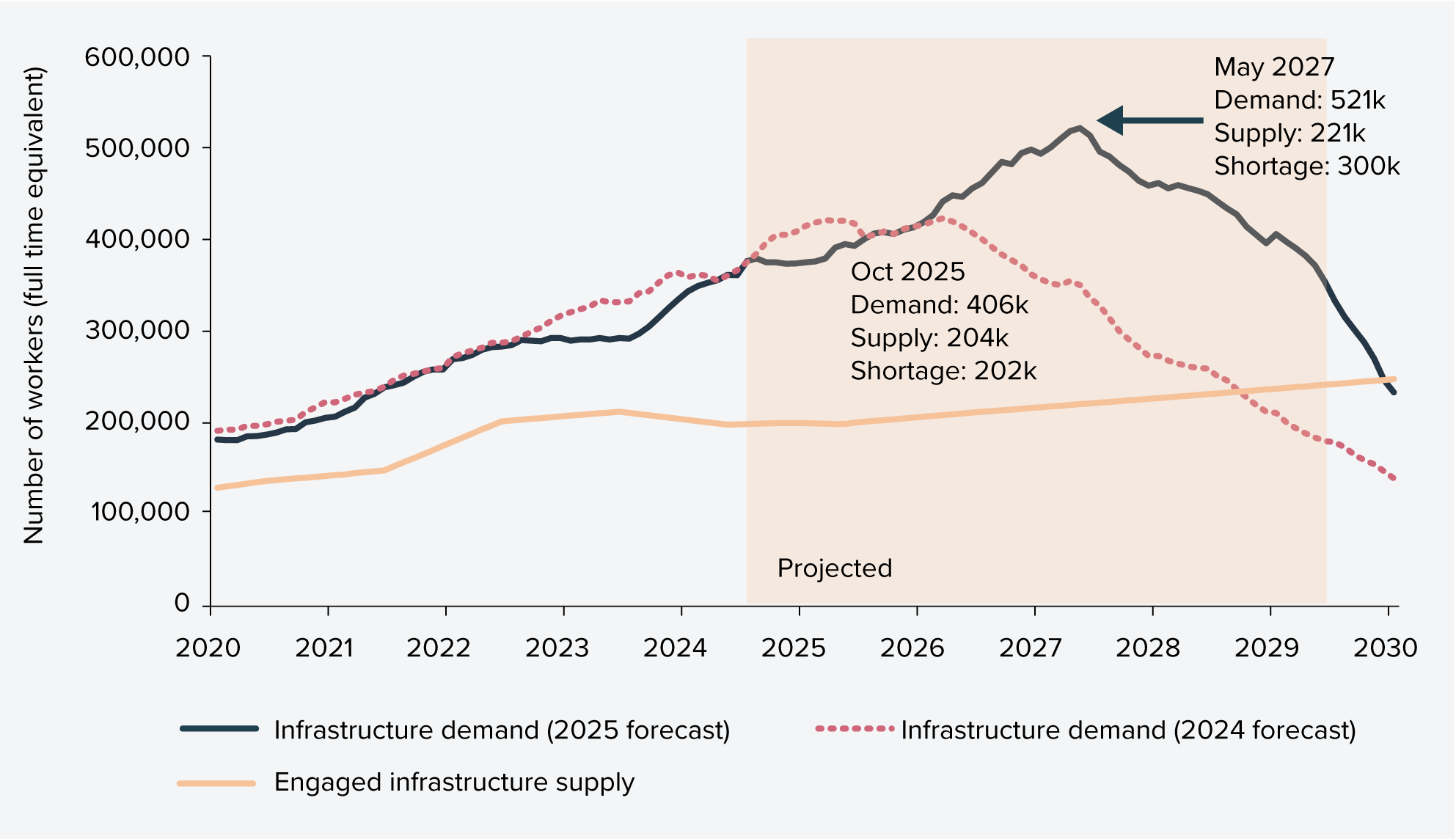

Peak workforce shortage could reach 300,000 as the sector faces both supply and skilling challenges

Labour remains the most critical delivery risk. After a brief easing in 2024, shortages are projected to surge and could reach 300,000 workers by 2027. Regional areas will be hardest hit, with shortages forecast to quadruple between 2025 and 2027.

The sector faces a dual challenge: filling critical roles in sustained short supply and upskilling the workforce for the digital and net zero transition. Industry soundings from in-depth interviews on the energy transition suggest that companies are adopting a cautious, ‘wait and see’ approach to workforce and skills investment, rather than committing to long-term training or efforts to boost baseline workforce supply. There is currently ambiguity around exactly how and the extent to which workers can transition across adjacent sectors to meet demand once materialised.

Various pilots and initiatives by governments, industry and the training and education sectors are underway to address construction workforce challenges. National alignment and coordination across these initiatives, and boosting industry confidence in the energy pipeline, will help firms invest more in building future workforce and capabilities.

Initial steps have been made to unpack the productivity problem, with further scope to examine the subcontracting ecosystem and incentives to embed innovation

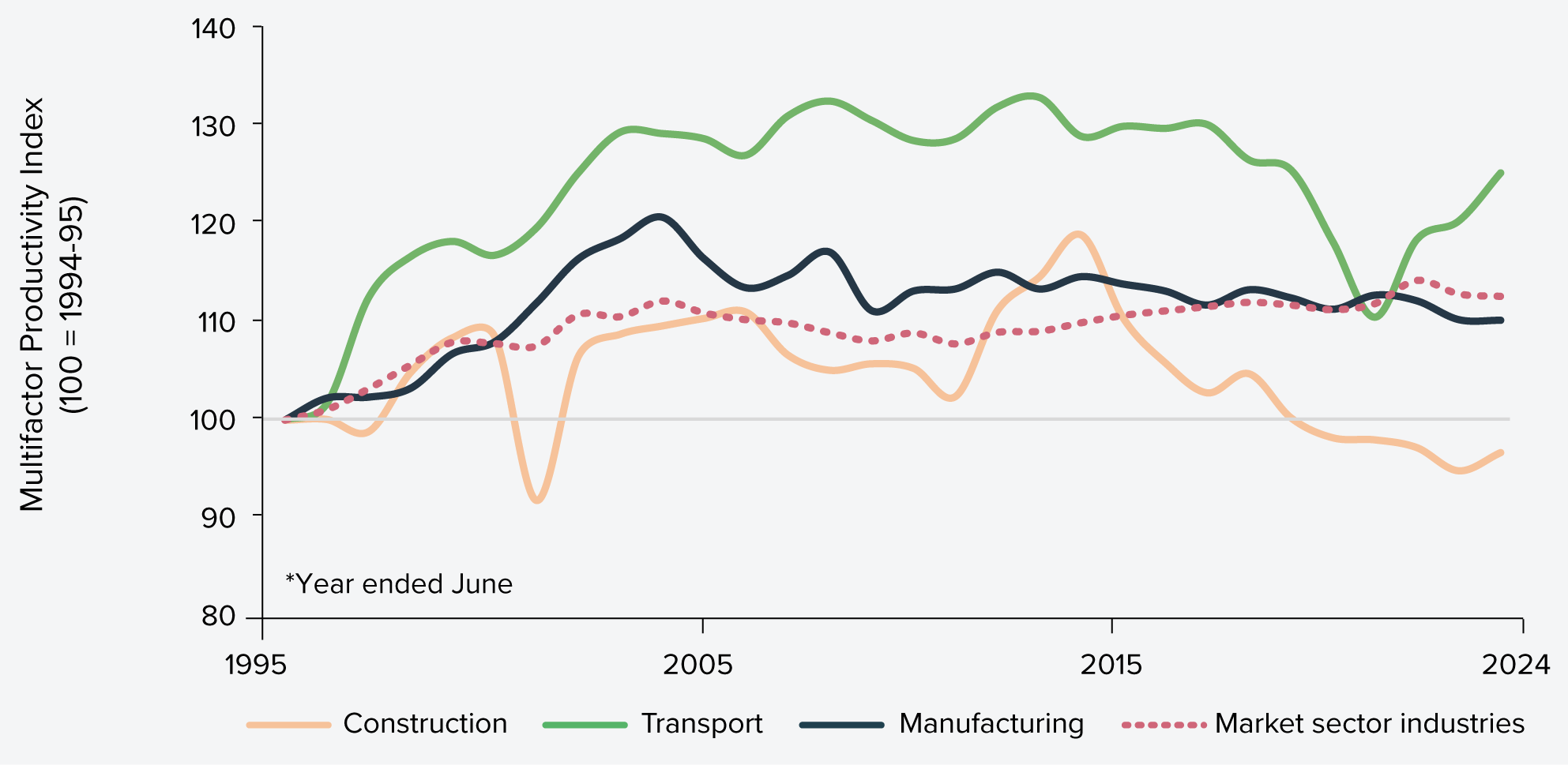

Productivity in Australia’s construction sector remains stubbornly low despite a short-term rebound, with multifactor productivity rising 2.0% in 2023-2024 after a decline the year before. The long-term trend is flat and well below mid-1990s levels.

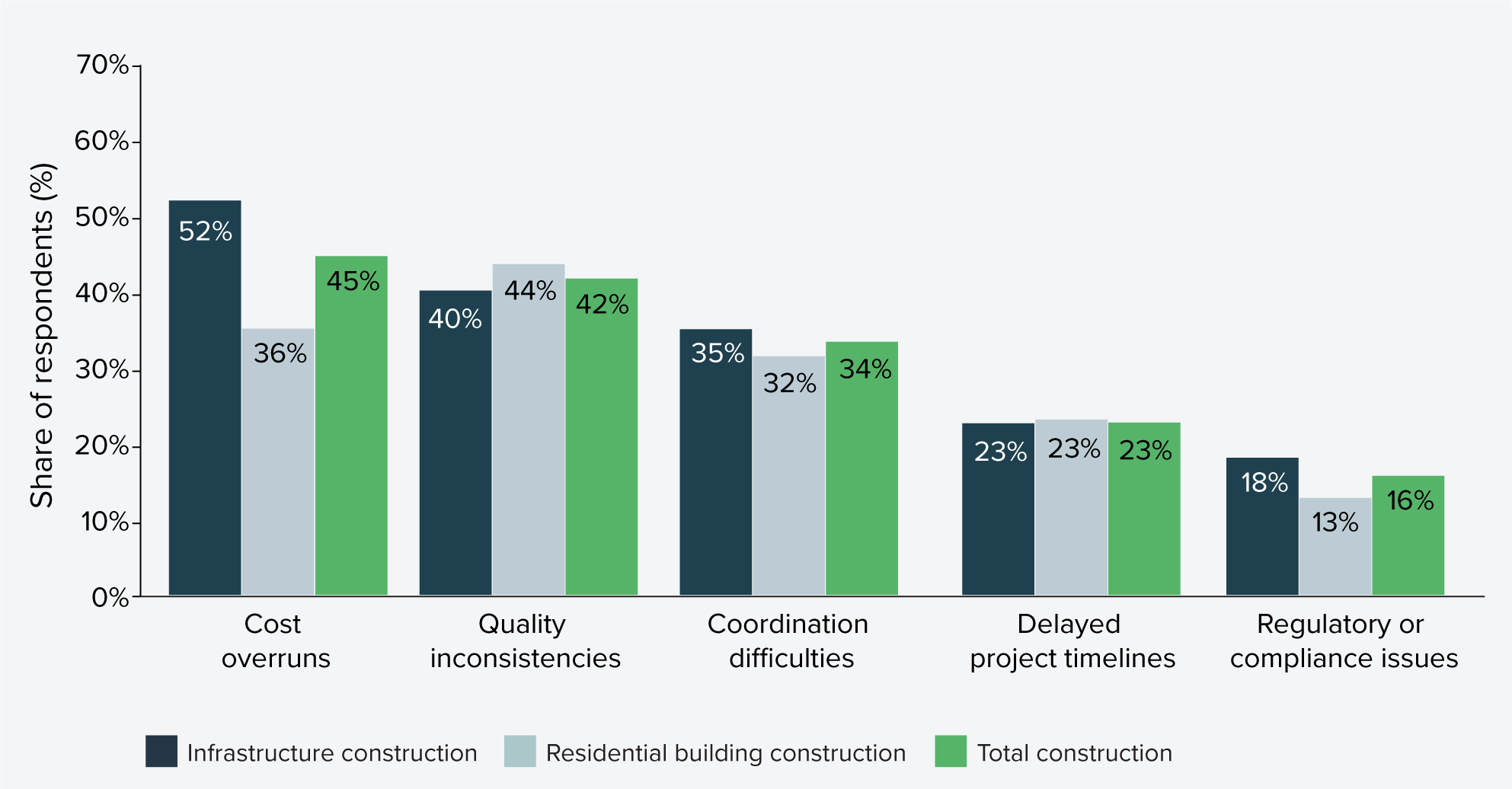

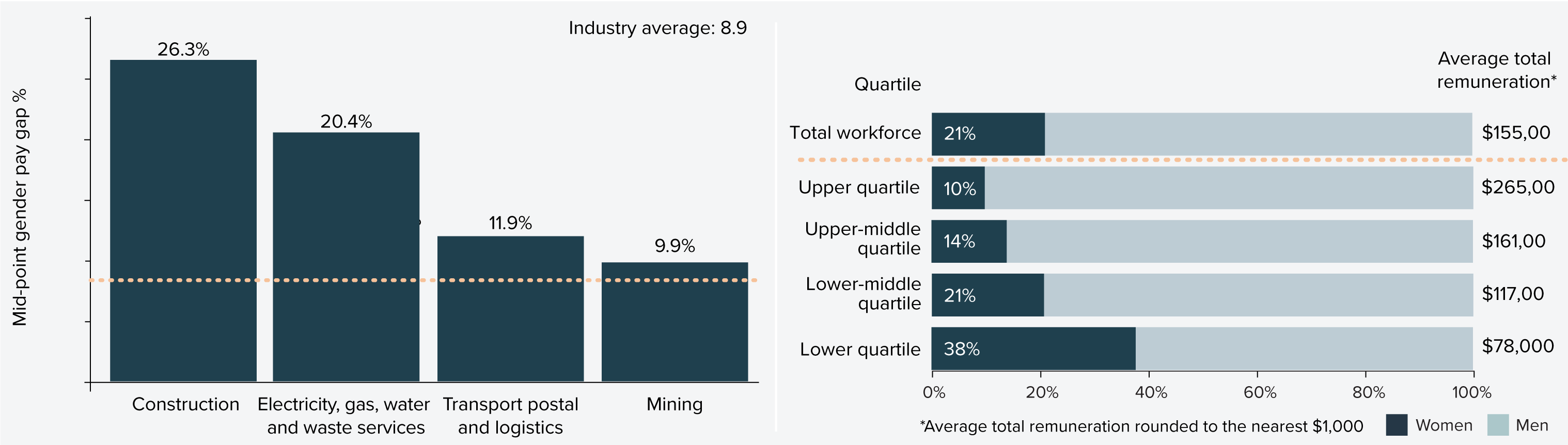

Structural issues persist: a heavy reliance on subcontracting (41% of infrastructure construction) introduces interface risks and erodes Tier 1 self-performance, while workforce diversity remains poor — women make up just 13% of the workforce and 4% of trades.

State, territory and federal governments are supporting the uptake of modern methods of construction, however prefabricated construction currently makes up less than 5% of the total market. Outside of dedicated modern methods of construction projects, prevailing procurement models focused on lowest cost discourage innovation that delivers long-term value. Regulatory and financing barriers may also impede modern methods of construction uptake, and the Australian Government is working to address these.

Two major national initiatives could drive change: the National Construction Strategy, due by end-2025, and the National Construction Industry Forum’s Blueprint for the Future, endorsed in September 2025. While these mark promising first steps to addressing systemic productivity challenges for construction, their real impact will depend on how they are implemented and the concrete actions that follow.

Progress made by governments over the last 12 months

Infrastructure is a necessary and key enabler to achieving key government priorities such as boosting national productivity, net zero transition and boosting housing stock. Over the past 12 months, governments have progressed significant initiatives and reform agendas which will help to strengthen the market’s capacity to deliver.

Key progress by the Australian Government across the four themes presented in previous iterations of the Infrastructure Market Capacity report:

Active pipeline management to mitigate delivery constraints — implementation of the new Federation Funding Agreement Schedule (FFAS) on Land Transport Infrastructure (2024-2029), which includes for the first time the collection of bilaterial performance reports from states and territories on progress against agreed policy priorities to enable outcomes that would boost supply (such as lift recycled materials uptake, skills training, workforce diversity). By tracking performance and setting benchmarks against these priorities, governments could prioritise projects that deliver the greatest strategic value and boost market capacity and capacity to deliver.

Separately, the Australian Government has committed to fast-track environmental approvals on clean energy projects and regional planning under Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) reforms and also commenced a new pilot of the Investor Front Door program (September 2025) to support delivery of transformational energy projects.

- Boosting materials supply — measures focused on supporting industry transition and boosting Australia’s competitiveness in the net zero economy, including major investments under the Future Made in Australia plan to expand domestic manufacturing, accelerate the adoption of low-emissions materials and maintain domestic steel manufacturing capacity at Whyalla Steelworks.

- Boosting labour supply — a raft of initiatives including expanding TAFE and apprentice incentives, national licensing reform of electrical trades and fast-tracking construction related assessments through the Skills Migration Framework.

Lifting construction productivity — the Australian Government is driving transformative reforms aimed at lifting national productivity across all sectors of the economy.

The construction industry will benefit from initiatives to cut regulatory red tape and promote national harmonisation of licensing, standards and certifications delivered as part of the National Competition Policy reforms and supported by the $900 million National Productivity Fund. Additionally, the Australian Government is investing $4.7 million to develop a voluntary national certification scheme to support offsite construction, streamline approvals and ensure high quality standards are met, and $49.3 million supporting state and territory governments to expand prefabricated and modular home construction opportunities.

A cornerstone initiative led by the Australian Government and targeted at the construction industry specifically — the National Construction Industry Forum’s Blueprint for the Future, developed by representatives across employers, workers and government — will drive nationally-coordinated actions to lift productivity across the sector. The blueprint outlines nine priority recommendations for reform, including cultural change, risk allocation and skills development, to tackle systemic inefficiencies and boost productivity across housing and infrastructure projects.

Recommended future opportunities for the next 12 months

Building on the progress made by governments over the last 12 months and updated insights on the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline, this report identifies opportunities for Australia’s governments to further strengthen market delivery capacity through pipeline management, boosting supply and lifting construction productivity. Table 1 sets this out in detail.

Table 1: Update on progress made over the last 12 months and future opportunities

| 1. Active pipeline management | |

|---|---|

| Progress over last 12 months | Current state – key findings |

National Renewable Energy Priority List established (March 2025), with listed projects receiving coordinated support from the Australian Government and state and territory regulators for approvals. Rewiring the Nation program has committed over $20 billion to upgrade and expand the electricity grid, with major transmission projects like HumeLink underway, concessional finance delivered via the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, and state partnerships supporting renewable integration and grid reliability. | Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline demand

Energy

|

| Future opportunities | |

1. Governments could further accelerate the energy transition by exploring options to:

| |

| 2. Boost materials supply | |

|---|---|

| Progress over last 12 months | Current state – key findings |

|

|

| Future opportunities | |

2. Governments could consider measures to ensure fabricated steel products used in infrastructure projects consistently meet Australian Standards by:

| |

| 3. Boost labour supply | |

|---|---|

| Progress over last 12 months | Current state – key findings |

|

|

| Future opportunities | |

3. Governments and industry could explore opportunities to coordinate and align emerging training programs across jurisdictions to accelerate the development of priority construction workforce skills in digital technologies, modern methods of construction, and decarbonisation. This alignment could include sharing lessons learned, promoting standard approaches to course design delivery and facilitating cross-jurisdiction recognition of prior learning for unaccredited training to improve workforce mobility. | |

| 4. Lift construction productivity | |

|---|---|

| Progress over last 12 months | Current state – key findings |

|

Subcontracting

Workforce diversity — women’s participation

Uptake of technology & modern methods of construction

|

| Future Opportunities | |

4. Governments could explore ways to embed innovation in infrastructure project delivery to unlock significant productivity gains across the construction sector. This could include:

| |

Introduction

The annual Infrastructure Market Capacity reports respond to a request made by the Prime Minister and First Ministers in 2020: that Infrastructure Australia work with jurisdictions and industry bodies to monitor the infrastructure sector.

“Leaders considered analysis on the market’s capacity to deliver Australia’s record pipeline of infrastructure investment to support the country’s growing population. This analysis highlighted the importance of monitoring infrastructure market conditions and capacity at regular intervals to inform government policies and project pipeline development. Leaders agreed that Infrastructure Australia will work with jurisdictions and relevant industry peak bodies to monitor this sector.”

Source: Council of Australian Government Communiqué,

20 March 2020

The fifth publication on infrastructure demand and supply from Infrastructure Australia

Like the previous four editions of the Infrastructure Market Capacity report, this report examines public infrastructure demand and market supply capacity over five years — in this case, 2024-25 to 2028-29. It provides an updated health check and analysis of our national construction market’s capacity to deliver public infrastructure works. The report is structured as follows:

- Understanding demand: a quantification of total infrastructure demand across five years by sector and project type, and detailed analysis of the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline including year-on-year changes and escalation costs.

- Non-labour supply: an appraisal of the main supply-side risks to market capacity today, including industry views gleaned from interviews and surveys conducted for this report. The focus is on materials supply, which is the largest non-labour supply category by cost shares.

- Labour and skills supply: estimates of infrastructure construction labour supply and shortage by jurisdiction and occupation groups.

- Industry productivity: analysis of the current state of the construction industry, including productivity trends, supplemented with industry perceptions obtained from our 2025 Industry Confidence Survey.

Continued emphasis on policy implications with acknowledgement of progress and looking ahead at future directions

The 2023 Infrastructure Market Capacity report introduced 14 recommendations across four areas to actively manage demand, boost materials supply, boost labour supply, and turn around construction productivity. The 2024 Infrastructure Market Capacity report provided an update of market capacity conditions and pointed to future directions for the Australian Government to maintain the momentum for work in progress. This 2025 edition does the same, using those same four recommendation areas to orient a summary of:

- progress to mitigate market constraints over the past 12 months,

- the current state of the market, and

- future directions for the Australian Government to maintain the momentum for work in progress.

A brief explanation of our Market Capacity Program

The Market Capacity Program is an assumptions-based methodology for identifying market capacity risks. It was developed in collaboration with state and territory governments, industry, advisory bodies and other subject matter experts. These partnerships are integral to the ongoing evolution of the Market Capacity Program.

The Market Capacity Program is underpinned by two system components:

The National Infrastructure Project Database

The National Infrastructure Project Database aggregates and organises infrastructure project data supplied by the Australian Government, state and territory governments (public investments), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (housing building activity) and GlobalData (private investments). The following infrastructure sectors are included in the Market Capacity Program:

- Buildings: non-residential buildings for health, education, sport, justice, transport buildings (such as parking facilities and warehouses), other buildings (such as art facilities, civic/convention centres and offices), detached, semi-detached, apartments and renovation activities (using all residential building activities captured in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Building Approvals).

- Transport: roads, railways, level crossings, and other transport projects such as airport runways.

- Utilities: water and sewerage, energy and fuels, gas and water pipelines.

- Resources: base metals, precious metals, critical minerals, hydrogen and ammonia, chemical and pharmaceutical plants, oil and gas, and ports.

Market Capacity Intelligence System

The Market Capacity Intelligence System is a set of analytical tools that interrogates and visualises project demand by sector, project type and resource inputs, for the following infrastructure pipelines:

- Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline: Publicly-funded infrastructure projects valued over $100 million in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia, and over $50 million in South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory and Tasmania.

- Small Capital Public Infrastructure Pipeline: Publicly-funded infrastructure projects valued $100 million and under in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia, and $50 million and under in South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory and Tasmania.

- Private Infrastructure Pipeline: Privately-funded public infrastructure, such as a wind farms, that are funded, delivered and operated by the private sector.

- Private Buildings: Residential and non-residential buildings projects.

- Road Maintenance: Resource demands for road-maintenance projects.

Industry confidence research

Supporting the quantitative analysis research each year, Infrastructure Australia also undertakes industry research to gauge industry confidence levels and better understand their perspectives on current market conditions. Three surveys were undertaken of Australian businesses in the building and construction industry, supplemented with in-depth interviews:

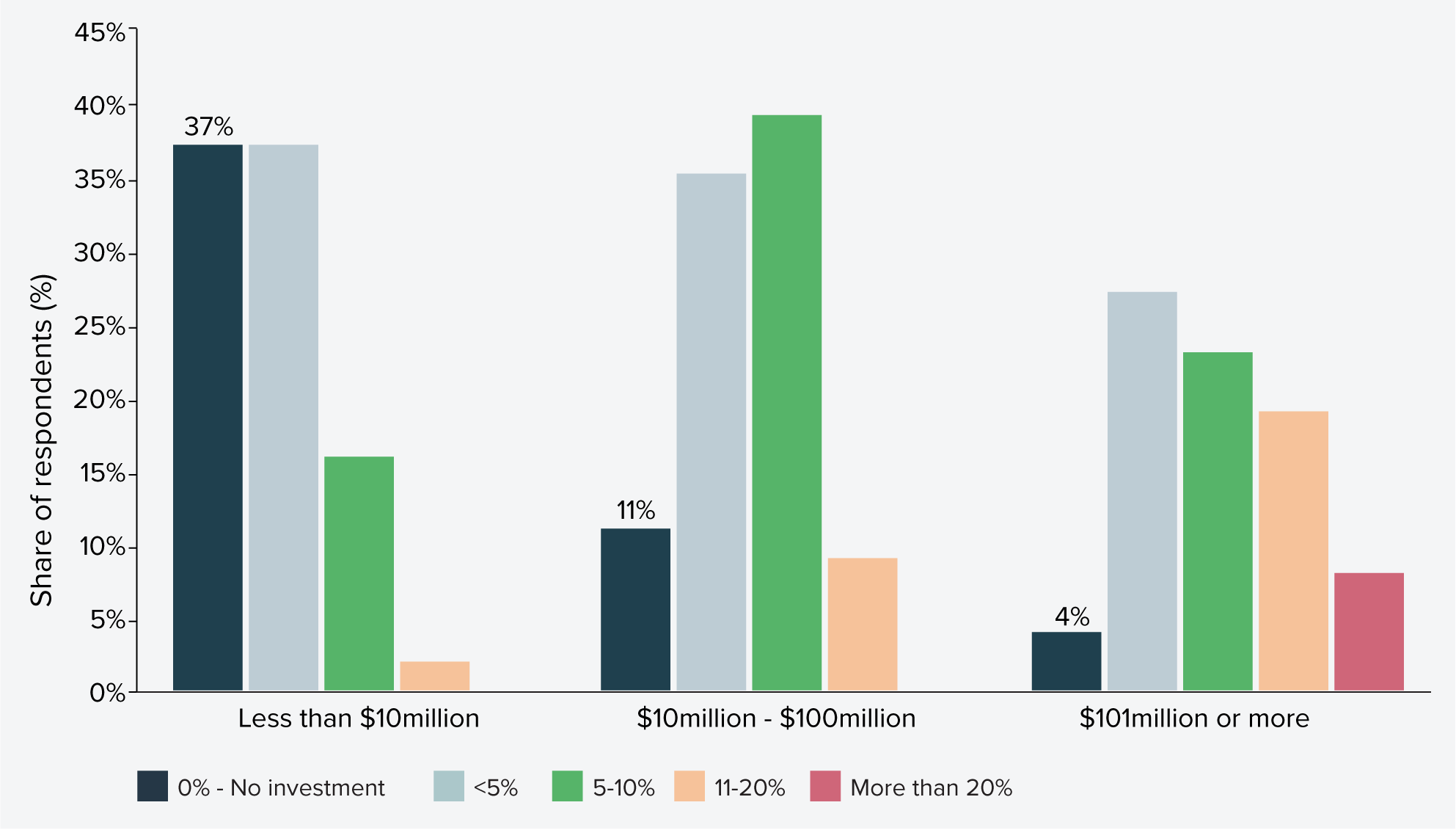

- The 2025 Industry Confidence Survey (n=200) captured views across the infrastructure life cycle, across identification/planning, design, construction, operations and management. The survey sample were actively delivering contracts that ranged in value from less than $10 million (64%), between 10m million and $100 million (23%), and more than $101 million (13%) over the last 12 months.

- The Civil Contractors Federation Survey of its members conducted in 2025 (n=134) captured views of civil construction businesses, comprised of majority (63%) smaller Tier-3 and Tier-4 businesses with annual turnover of less than $100 million.

- In-depth interviews (n=20) with randomly selected building and construction businesses, with each tier represented, to get a more detailed understanding of the key issues for the year.

All states and territories were represented in this year’s industry surveys, with responses broadly reflecting the geographic distribution of the construction industry — most in New South Wales and Victoria, followed by Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia, and the smaller jurisdictions Australian Capital Territory, Tasmania and the Northern Territory.

Detailed methodologies in Appendices

See the Supporting Appendices for detailed explanations of the Market Capacity methodology:

- Appendix A: Demand-side analysis methodology

- Appendix B: Supply-side analysis methodology

- Appendix C: Infrastructure typecasts

- Appendix D: Resource classifications

- Appendix E: Workforce and skills methodology

- Appendix F: Industry confidence surveys

SECTION 1 SUMMARY: Understanding demand

Active demand management - future opportunities

- Governments could further accelerate the energy transition by exploring options to:

- Enhance future updates of the National Renewable Energy Priority List with more detailed project level information — such as funding committed, planning milestones, and delivery stages. This could provide industry with greater certainty about the forward pipeline, supporting more effective planning, investment, and capacity building across the supply chain.

- Establish an environmental approvals concierge, similar to the Investor Front Door function under the Future Made in Australia package, to provide early guidance and facilitation for significant infrastructure projects. This concierge could:

- help state and territory government proponents identify whether EPBC Act approval is required during early project scoping,

- clarify and promote the use of bilateral assessment pathways, and

- connect proponents with relevant Australian Government agencies and resources to facilitate the approval process

Summary

- The Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline (MPIP) has grown to $242 billion for 2024–25 to 2028–29, up 14% from last year’s outlook, reversing previous declines.

- Growth is driven by new projects added to the pipeline, particularly in housing and energy transmission.

- Transport remains the largest category at $129 billion (53%), while buildings have increased to $77 billion (32%), led by residential and health projects.

- Utilities investment has more than doubled to $36 billion (15%), reflecting the addition of several large transmission projects.

- The demand profile shows peak investment shifting to 2027, with stronger certainty in outer years compared to previous reports.

- Regional demand is rising sharply, especially in Queensland, Northern Territory, South Australia, and New South Wales, with some regions expected to more than double current construction activity in the next four years.

- The slow progress on privately funded renewable energy projects from planning to delivery continue to delay the anticipated ramp up in demand for resources into the future, creating uncertainty and slowing workforce investment.

SECTION 1: Understanding demand

More than a trillion dollars in construction activity anticipated over five years is captured in Infrastructure Australia’s data

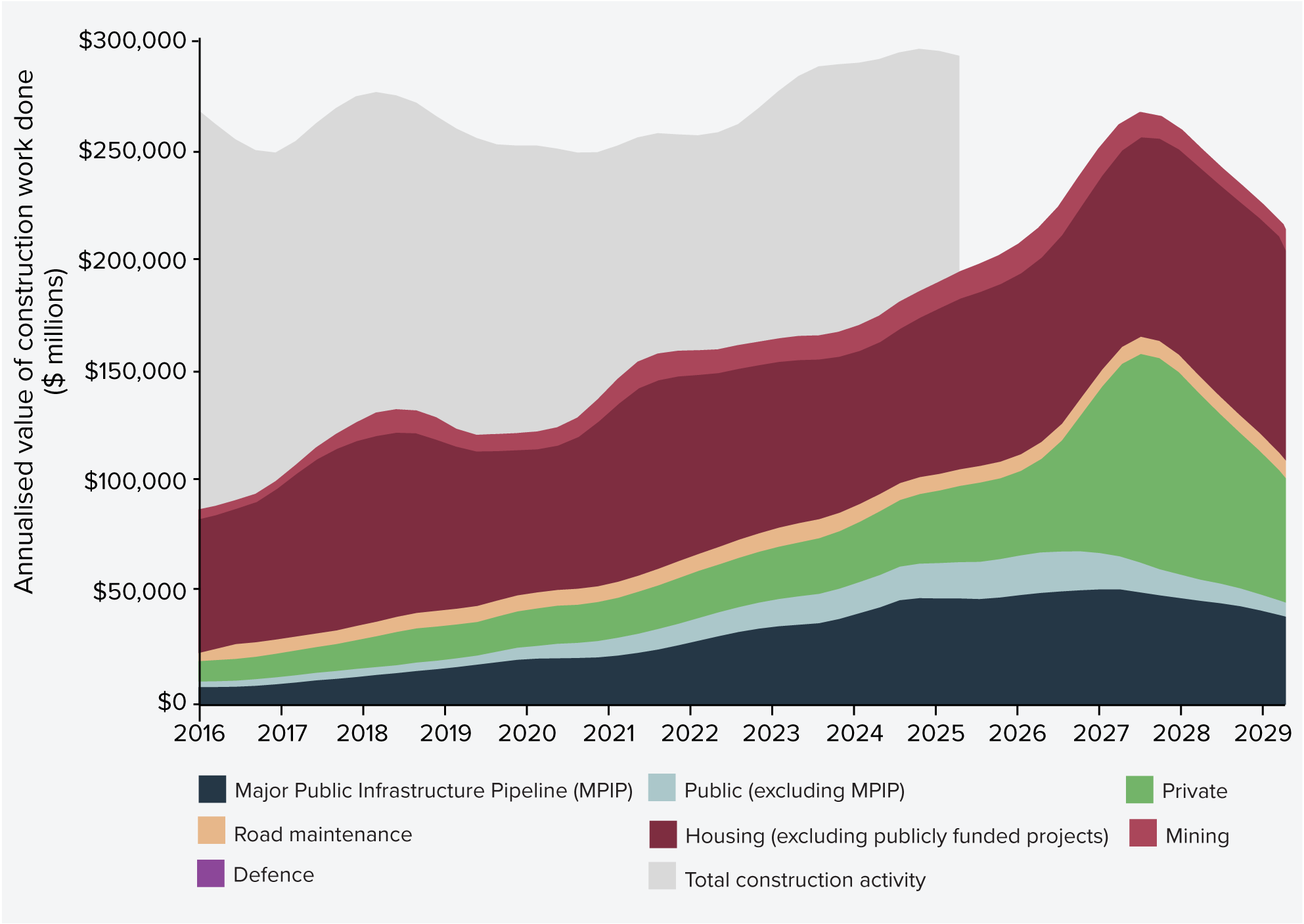

Figure 1 shows Australia’s forecast of construction activity based on project cost estimates, compared against total construction activity reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). The key distinction is that ABS data (shown as ‘Total construction activity’) reflects actual costs, including the impact of cost escalations, whereas Infrastructure Australia’s database (comprising the ‘MPIP, SCPIP, Road Maintenance, Mining, Private, and Housing pipelines) uses cost estimates with limited certainty about future escalations. This difference makes it challenging to determine the exact share of total activity captured by our forecast. However, this comparison does indicate our forecast construction volumes peaking in 2027 at levels comparable to current ABS-reported activity.

While not all projects in our database are expected to proceed as announced, this provides valuable insight into market ambition over the coming years.

Figure 1: Forecast construction spend, as captured in the Infrastructure Australia database, against a backdrop of historic total construction activity (2016 to 2029)

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (for total construction activity)5

Total construction demand captured in our database covers $1.14 trillion in the five years from 2024–25 to 2028–29. This level of forecast activity is almost in line with current run rates where the total construction activity reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in the five years from 2020–21 to 2024–25 was $1.4 trillion.

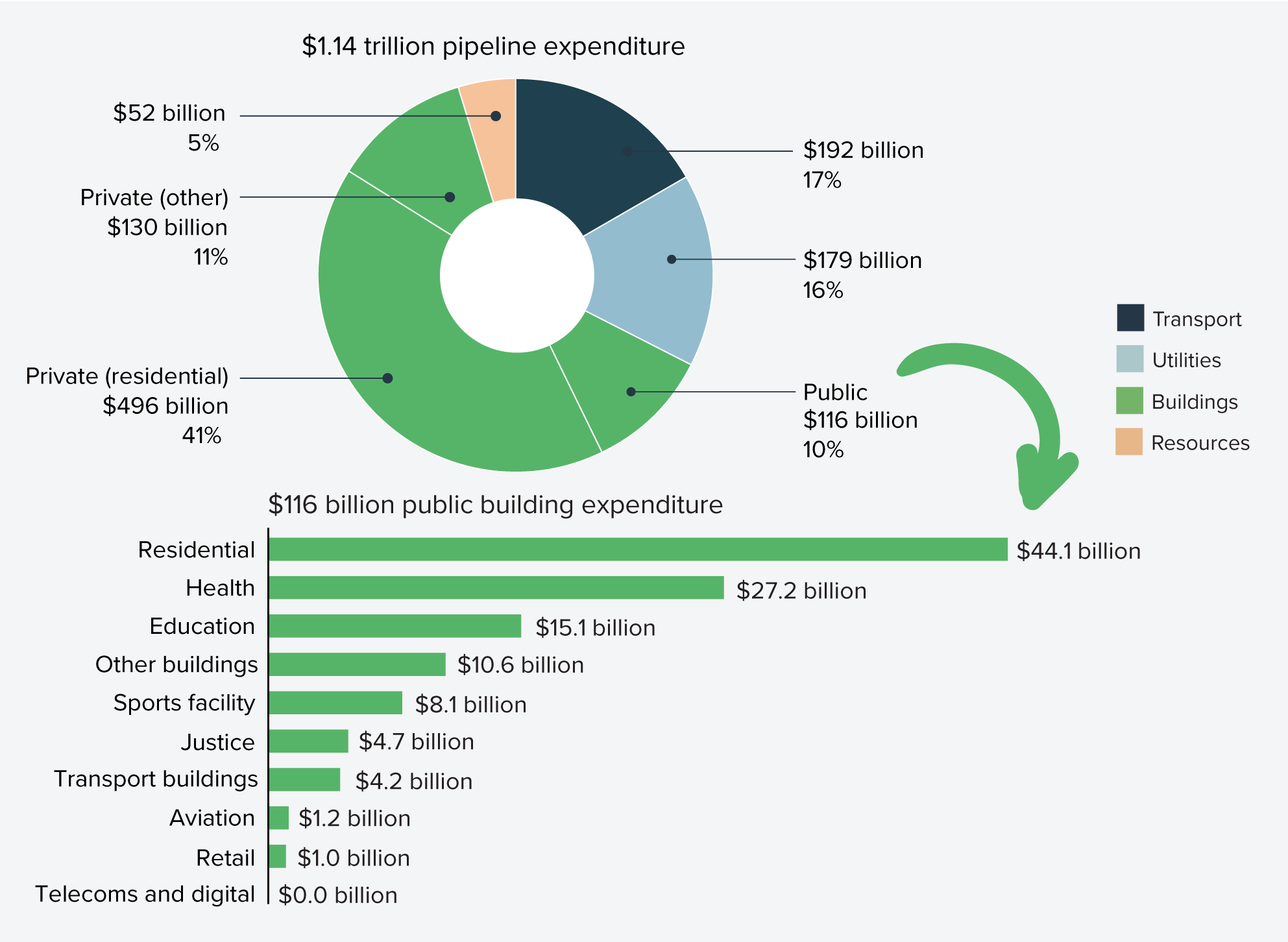

Figure 2 shows the total infrastructure pipeline, as captured in our database, broken down by sector. Buildings account for most of the expected expenditure (62%), followed by transport (17%), utilities (16%) and resources (5%).

Of the $716 billion in buildings, $77 billion is from the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline, with another $48 billion invested in smaller capital buildings projects by governments, totalling $116 billion of public investment. Figure 2 includes a breakdown of this public investment in buildings, which is dominated by residential and health projects.

Figure 2: Combined construction pipeline, as captured in the Infrastructure Australia database, by sector (2024–25 to 2028–29)

For the period 2024–25 to 2028–29, public spending accounts for 28% of the $1.14 trillion construction market, of which the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline totals $242 billion (22%) and $66 billion (6%) is planned on Small Capital Projects. The rest of this chapter provides an analysis of the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline.

The five-year Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline has increased by 14% to $242 billion, reflecting national priorities for housing supply and the energy transition

The five-year rolling Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline has increased from $213 billion projected last year (2023–24 to 2027–28) to $242 billion this year (2024–25 to 2028–29).

This increase reverses the trend previously observed in 2023 and 2024 where year-on-year reductions in forecasted spending were reported:

- 2023 Infrastructure Market Capacity reported $230 billion down from $237 billion in 2022.

- 2024 Infrastructure Market Capacity reported $213 billion down from $230 billion in 2023.

The rise is reflective of national priorities to supply more housing and accelerate the energy transition. For publicly-funded projects we continue to see the transport portfolios across Australian states and territories hold steady, with governments continuing to grow investments in buildings, particularly for health and housing outcomes. Meanwhile, the growth in public-funded utilities infrastructure is predominantly explained by the addition of transmission projects in support of the energy transition.

Peak investment has moved one year out to 2027 compared to the projection last year. These changes are consistent with a continuing trend each year where the projected investment peak shifts into outer years.

The profile of demand over the five years has flattened compared with the 2024 profile. In fact, for the first time, our reporting shows that the outer year, 2028-29, falls away to a level that is more than 75% of the peak. In prior years, this drop in outer years has been anywhere between 50% and 60% of the peak. While this does not translate to long-term project certainty, it is a strong indication of long-term investment certainty in public infrastructure projects.

Like-for-like analysis of how project estimates have changed in the past 12 months shows the growth in demand is primarily driven by projects recently added to the pipeline

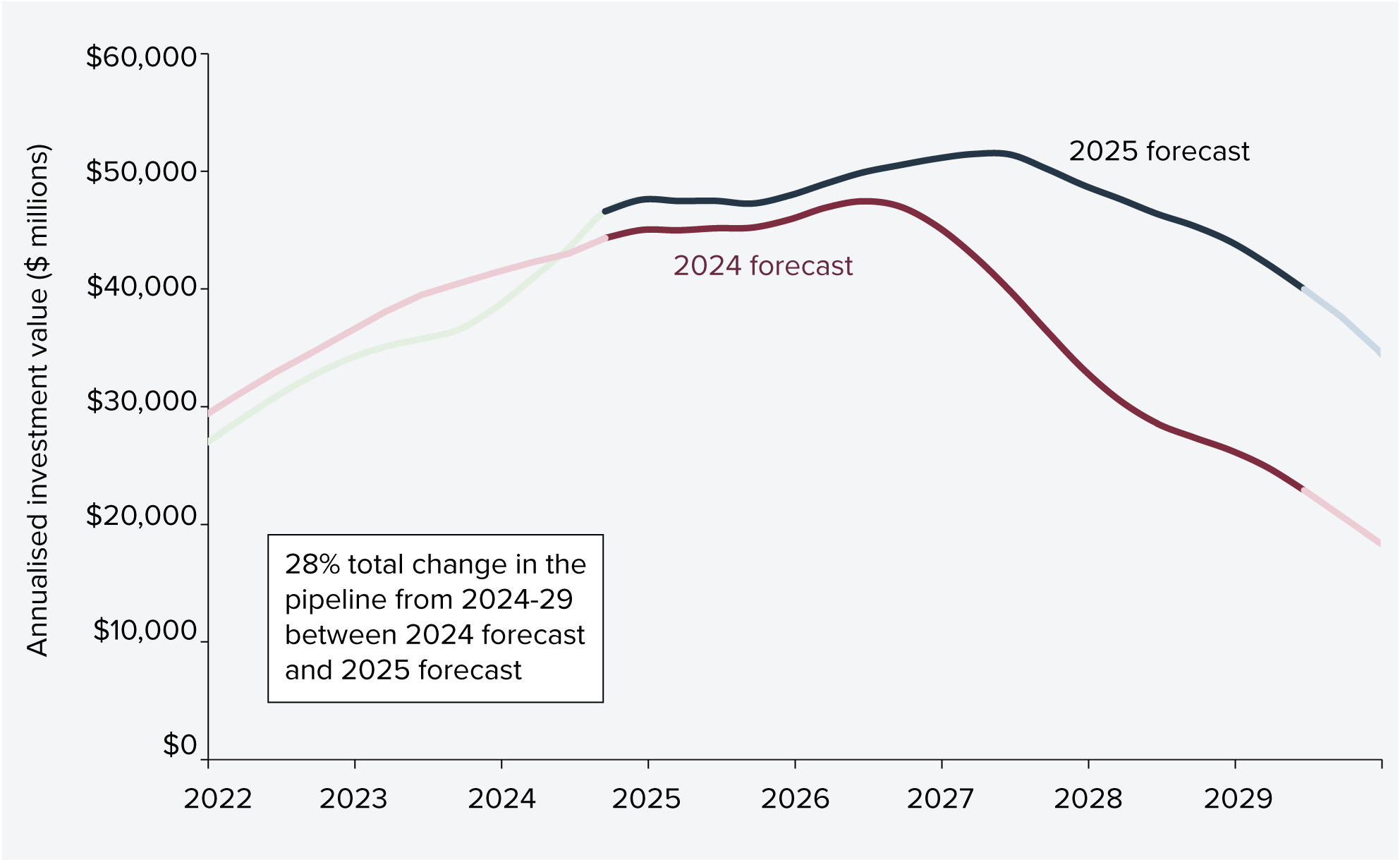

Infrastructure Australia conducted an in-depth year-on-year analysis, looking for differences in the investment schedule for projects in the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline between 2024 estimates and 2025 estimates over the same five-year period (2024-25 to 2028-29 as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparison of 2024 and 2025 forecasts of Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline activity (2024–25 to 2028–29)

Whereas the change in the rolling Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline described earlier is a 14% increase in activity from $213 billion to $242 billion, this like-for-like analysis is different because it is undertaken on the same time horizon for both the 2024 and 2025 forecasts without rolling on by one year, so the proportion of the 2024 forecast analysed is $189 billion.

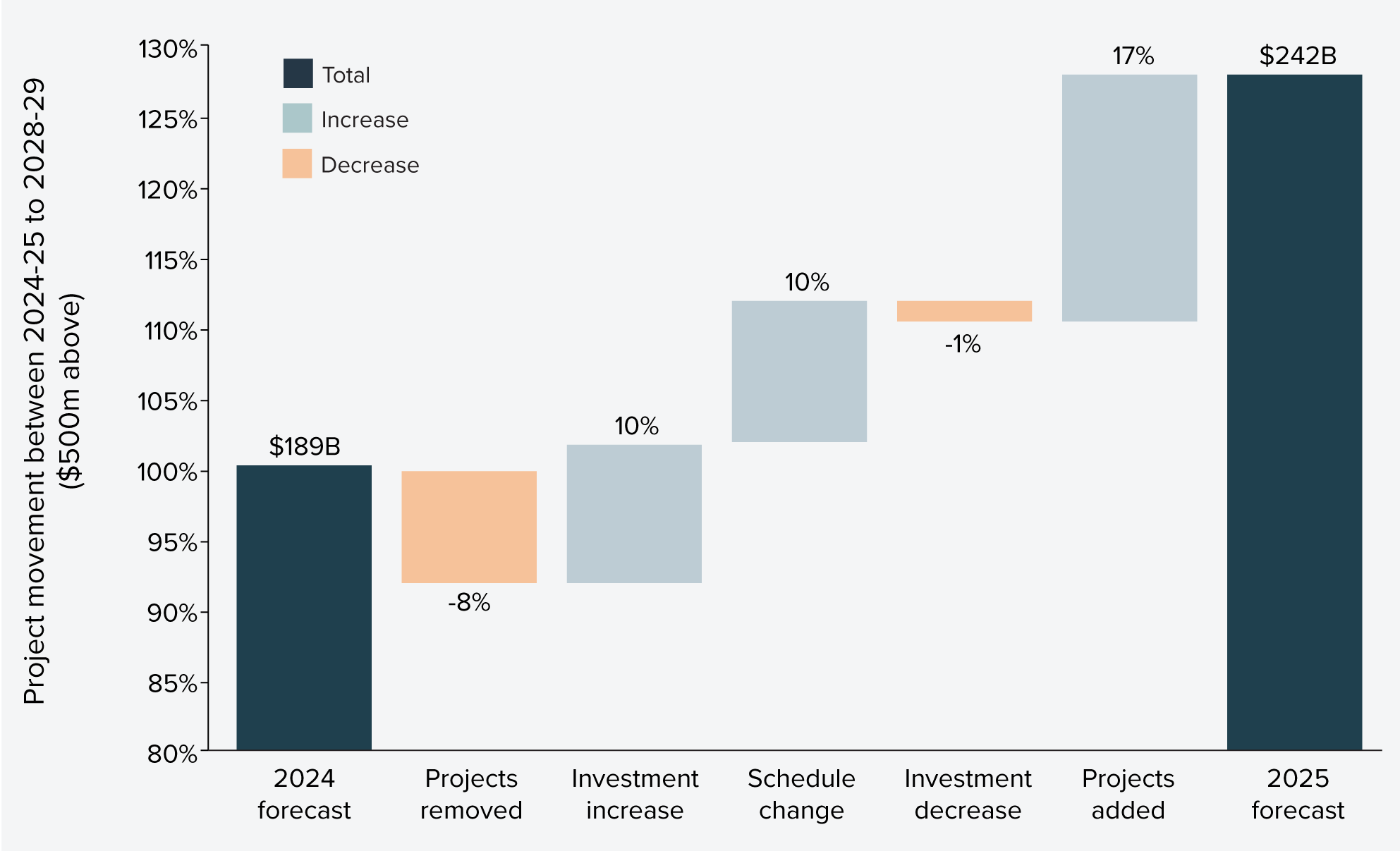

The analysis reveals the pipeline decreases by 8% due to projects being removed or recently completed, as shown in Figure 4. A further 1% drop was observed from investment cuts in continuing projects. At 9% down, this is significantly less than the 23% reductions observed 12 months earlier for both categories.

Increases to the pipeline were driven primarily by new projects coming into the pipeline (17%) which is well up on the previous year, while the increase explained by investment estimates (10%) was broadly in line with changes observed in prior years.

The remaining category that drives a change when comparing year on year, is explained by schedule changes to projects, where construction start and/or completion is delayed. This has the effect of lessening the investment in the time period that has already passed (2023-2024), and propping up the investment planned for the outer years of the time periods compared. It results in a 10% increase versus 2024 estimates.

Figure 4: Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline spend from 2024–25 to 2028–29, changes from 2024 forecast to 2025 forecast

In summary, this year’s growth in the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline is largely explained by many more new projects being added, compared to what has rolled off the pipeline from project completions and cancellations. Other categories are broadly in line with the findings from previous years, however it is noted that there was significantly less change attributable to decreases in a project’s investment, an indication that there was less focus on de-scoping within projects throughout the past 12 months than was observed in the year prior.

Analysis of demand by region sees further growth across northern Australia

Regional analysis is enabled by the development in 2023 of analytical tools built by Infrastructure Australia in partnership with governments across the country. These analytical tools are designed to help government decision makers diagnose labour supply bottlenecks, spot growth opportunities, and build strong evidence bases for investment decisions.

In the five years from 2024-2025 to 2028-2029, there are significant increases in public investment across Queensland and Northern Territory for the second consecutive year with Major Public Infrastructure Pipelines growing by another $4 billion to $51 billion, after a $16 billion increase the year before.

In Queensland the increases are driven by investments across the transport and utilities portfolios, predominantly explained by additional construction activity in the Sunshine Coast and Wide Bay regions. The upcoming demand for construction from 2025-26 to 2028-29 across these two neighbouring regions is more than four times that of the previous four years from 2021-22 to 2024-25.

In the Northern Territory the increase is driven by transport investment in the Greater Darwin area.

Growth across either housing or energy is evident in all states and territories

The jurisdictions driving an even higher proportion of the overall increase this year are New South Wales and South Australia with an additional $26 billion in the five-year outlook compared with the year before.

In South Australia the increase is driven by investments into housing across the Greater Adelaide area, while the transport portfolio increases as construction activity ramps up during the outlook period on its River Torrens to Darlington Project.

In New South Wales the increase is driven by the utilities portfolio with water and transmission projects added to the pipeline.

While most energy projects in the pipeline are privately-funded and therefore not counted in the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline, governments across Australia are putting significantly more investment into transmission. Transmission projects now account for $15 billion across the five-year outlook, up from $4 billion the year before. The increases are observed across five of eight states and territories.

Similarly, investment into social and affordable housing as part of the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline has increased and is now $28 billion up from $17 billion. When also considering smaller capital projects, there are six out of eight jurisdictions that have increased their investment into housing.

Figure 5: Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline spend by sector (2024–25 to 2028–29)

The projected increase in demand for many regional areas would intensify local supply chain constraints such as attracting workers and sourcing materials

The Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline comprises $63 billion of activity outside of Australia’s eight capital cities, which at 27% of the pipeline is broadly in line with Australia’s population distribution. This is up from $58 billion last year which means the increase is in line with the size of the increase across capital cities.

Unlike most capital cities, 10 regions across Queensland, New South Wales and Tasmania face a significant challenge with the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline in each expected to more than double between 2025-26 and 2028-29, compared with the previous four years (2021-22 to 2024-25). For this analysis, Infrastructure Australia uses Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Statistical Area 4 as the boundary between regions. Of all 41 regions outside of capital cities, 23 of them will see an increase in construction activity in the coming four years across, and these regions are located across all six states and the Northern Territory.

The challenges to be overcome with respect to the growing construction demand outside of capital cities are more pronounced when analysing the energy pipeline.

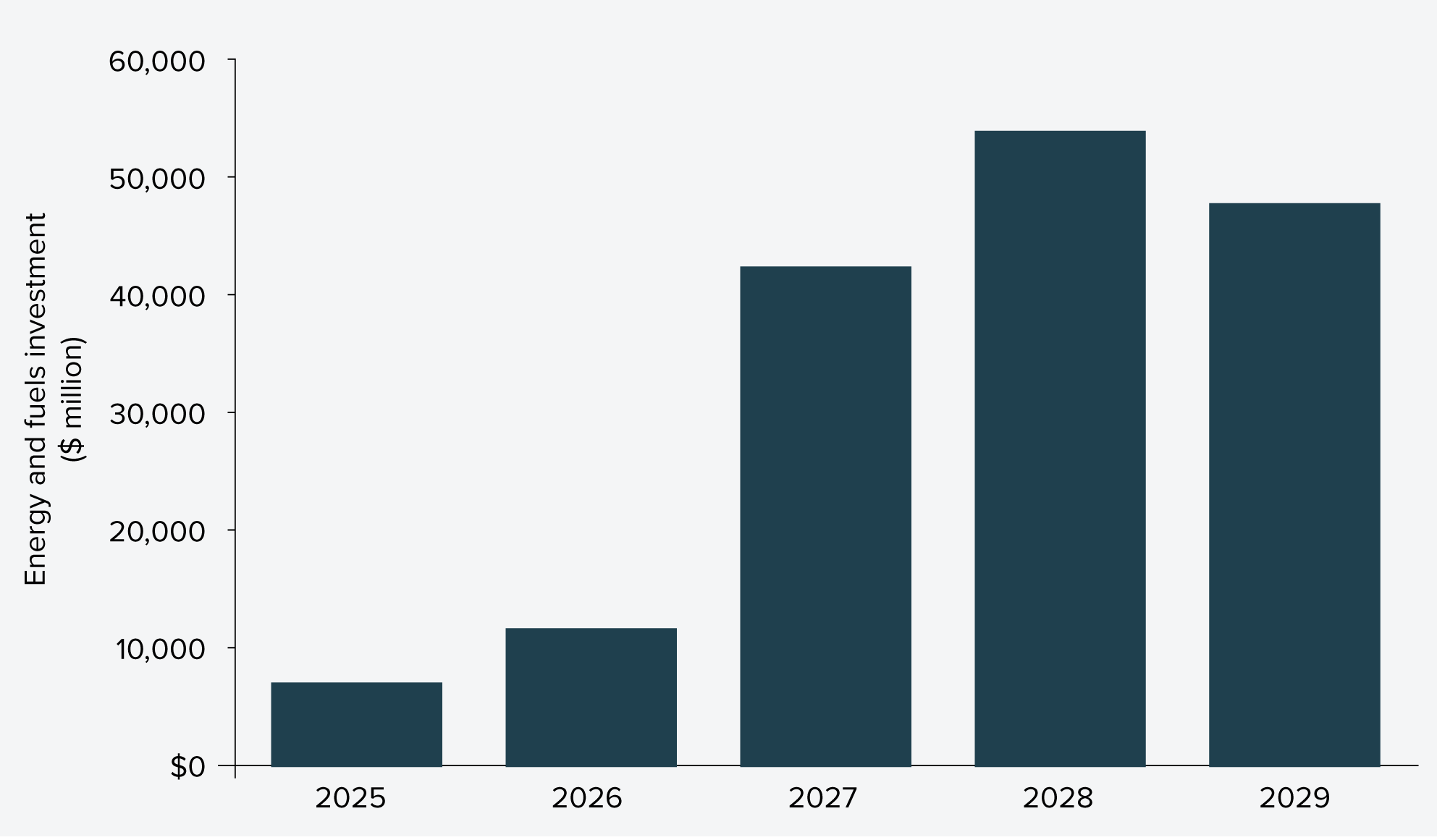

The Energy Pipeline

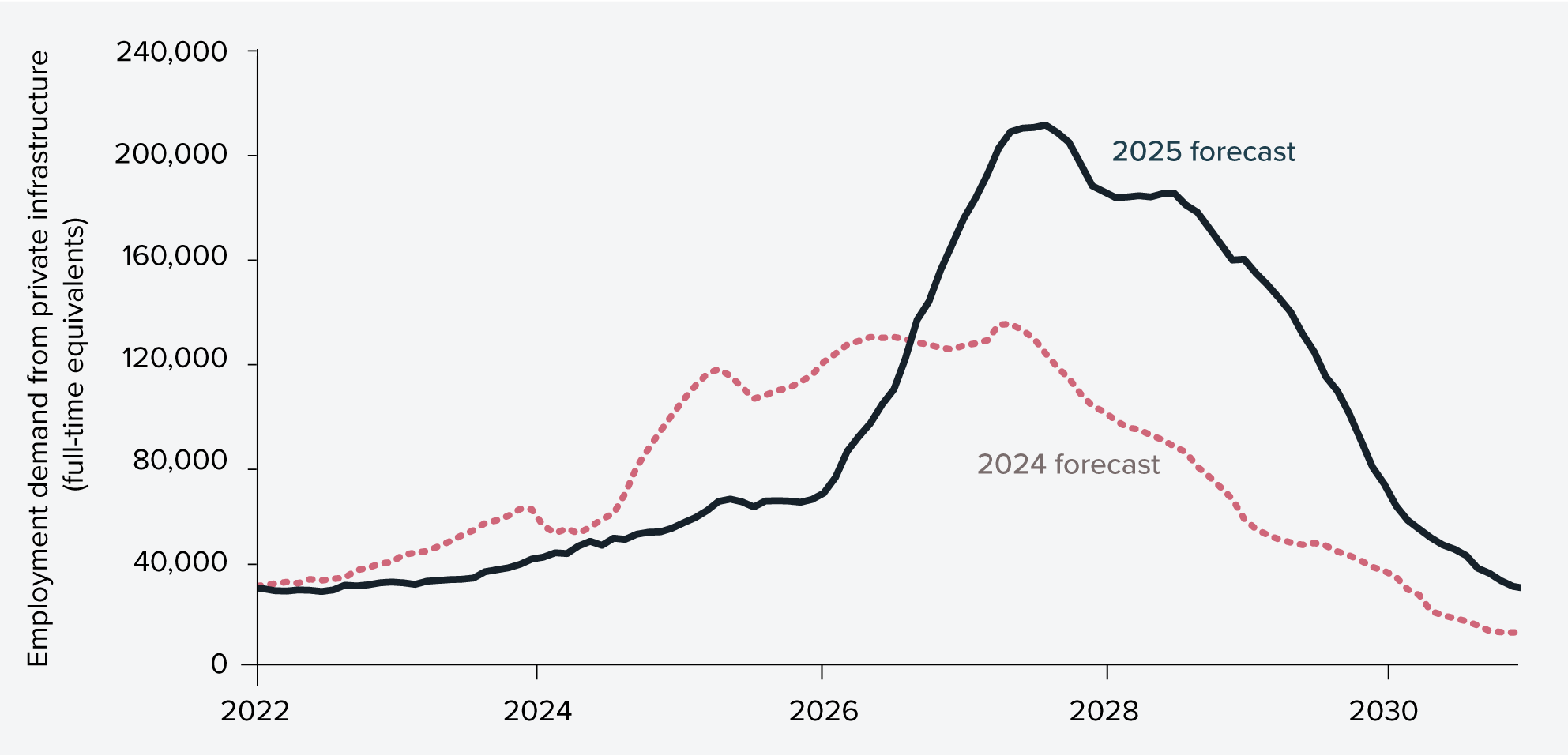

In terms of private investment (that is, not counted in the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline) we again observed a jump in labour demand much like that observed in the previous edition of this report. This step-change in labour demand is driven by the renewable energy transition. However, this year’s demand profile shows workforce demand now projected to rise sharply from early 2026, around 18 months later than earlier forecasts, which had anticipated growth from mid-2024, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Comparison of 2024 and 2025 forecasts of demand for labour from private infrastructure

Notes: Chart represents forecast labour demand data based on private infrastructure, excluding resources

The scale and pace of ambition in the pipeline faces delivery challenges

It is clear that energy infrastructure investment continues to shift to the right due to delays to the planned delivery timelines initially expected by project developers.

This is reinforced by analysis from Infrastructure Partnerships Australia of the Australia and New Zealand Infrastructure Pipeline (ANZIP — see below). Infrastructure Partnerships Australia has assessed the likelihood of energy projects achieving planned delivery schedules based on a range of criteria including the status of project financing, planning approvals, final investment decisions and signing of contracts. The results of this analysis were clear, that publicly-procured road, rail and social projects are much more likely to stick to their plans than energy projects. The analysis characterises 58% of the 298 energy projects included on ANZIP as having a low to moderate likelihood of being delivered to the project schedule, relative to the other energy projects on ANZIP.6

About the Australia and New Zealand Infrastructure Pipeline (ANZIP)

The ANZIP is produced by Infrastructure Partnerships Australia as a continuously updated forward view of major infrastructure projects and contracts across Australia and New Zealand. It provides a transparent, detailed and independent snapshot of infrastructure project investment, construction, operation and privatisation opportunities that Infrastructure Partnerships Australia tracks from announcement to completion.

The key distinctions between Infrastructure Partnerships Australia’s ANZIP and IA’s National Infrastructure Project Database analysed for this report are best explained by these two factors:

- ANZIP tracks projects from their early stages of planning, through to contract award, and into their operational phase, this means there is more breadth to project information retained in ANZIP.

- ANZIP’s Australian projects cover projects and operations that are A$300 million and over, and Public Private Partnerships and investable projects and divestments that are A$100 million and over. This means there are less projects in ANZIP than analysed in IA’s database.

Notwithstanding delivery challenges, the ambition for investment in energy projects continues to grow, with a focus in regional areas

As the net zero transition accelerates, the scale of energy infrastructure investment continues to grow. Irrespective of how it is funded, the pipeline for projects to build transmission, solar, wind and pumped hydro is now $163 billion for the five years from 2024-25 to 2028-29, as shown in Figure 7. Demand is expected to be most acute for regional Australia.

Figure 7: Forward pipeline of energy infrastructure investment (2024-2025 to 2028-2029)

Pipeline visibility, accelerating approvals and smoothing supply chains are all key to remove barriers to delivery of energy projects

State and territory governments have made significant strides to provide industry with better visibility of the forward pipeline for major public infrastructure such as transport.7 However, there is no equivalent for the energy sector, which is predominantly private industry-led and as such lacks coordination and is subject to greater commercial sensitivities.

The Australian Government, working with States and Territories, released the inaugural National Renewable Energy Priority List in March 2025. The List identifies 56 priority renewable energy projects that will receive targeted support to streamline regulatory planning and environmental approval processes. However, the list does not include information on funding commitments nor on delivery timelines, limiting industry’s ability to plan, invest, and scale delivery capacity with confidence.

Industry also often cites long planning and regulatory approval times and ‘green tape’ as barriers to progressing energy projects as planned. Almost half all organisations surveyed by Infrastructure Australia this year viewed delays in obtaining planning and environmental approvals (47%) as being among the greatest risks to project delivery.

Industry soundings suggest that in the face of these delays and likelihood that projects will proceed as planned, investors are directing money to overseas renewable energy opportunities and the overseas suppliers may be less willing to service the Australian market when they receive orders for their projects. Local firms are also hesitant to build workforce capacity for work that is yet to fully materialise.

Renewable energy supply chains also face enabling infrastructure and logistical challenges. The import and local transport of large components such as wind turbines can be constrained by existing port or road infrastructure. Some projects face difficulty getting off the ground due to a lack of capacity to connect to the grid. For example, for the South-West Renewable Energy Zone (REZ) in NSW, projects in the pipeline would theoretically deliver 16 gigawatts (GW) of generation capacity. However, the REZ has a maximum capacity cap of 3.98 GW that planned transmission can support.8

INDUSTRY SOUNDINGS

“Two years ago, we were doubling down on gearing up our energy teams ... [now] we are redeploying some of that capacity into parts of Asia and other locations where we are seeing the volume of work hitting the market much more quickly.”

(Constructor)

“All these new entrants to the Australian market are used to developing a couple of hundred-megawatt wind farm somewhere where the legislation requirements, the environmental constraints and the grid connection restraints aren’t as harsh. It’s just harder to do business in Australia because of the regulatory process.”

(Constructor)

Governments are streamlining approvals for energy projects

At the national level, the Australian Government has committed to reforming the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) to strengthen environmental protection and streamline approvals. It has committed to introducing the reform package to Parliament in 2025, six months ahead of the original timelines. Regional planning pilots are also currently underway in Queensland, South Australia Victoria and New South Wales. These pilots are providing information and guidance to help streamline assessments and approvals. Some pilots may be developed further to make regulatory plans that allow renewable energy projects in pre-assessed zones to bypass lengthy case-by-case approvals.

State and territory governments have also introduced a range of measures to fast-track approvals for energy projects in response to growing renewable energy targets and infrastructure needs.

For example:

- Western Australia has established a Priority Approvals team to coordinate inter-agency processes, enable parallel assessments, and provide a single point of contact for proponents, reducing delays and improving transparency.

- Similarly, Victoria’s Development Facilitation Program accelerates approvals for renewable energy and storage projects, guaranteeing decisions within about four months to help meet decarbonisation goals.

- The Northern Territory introduced its Approvals Fast Track Taskforce and Tasmania has introduced the Renewable Energy Approvals Pathway (REAP) to accelerate large-scale renewable projects like wind farms and transmission lines.

- Other states, such as New South Wales and Queensland, have implemented planning acceleration programs and priority development areas to cut red tape for critical infrastructure, while still maintaining environmental standards.

Under the EPBC Act, the Australian Government can enter into bilateral agreements with states and territories to streamline environmental assessments for projects that may impact matters of national environmental significance. These agreements allow a state or territory to conduct a single accredited assessment process that meets both state and federal level requirements, reducing duplication and improving efficiency. After the state or territory completes its assessment, it provides a report to the Australian Government, which then makes the final approval decision under the EPBC Act.9

This framework aims to balance high environmental standards while enabling timely project delivery by aligning assessment processes across jurisdiction. While bilateral agreements have been in place with all states and territories since 2015, their application remains low. More could be done to promote the use of the bilateral agreements to streamline approvals processes and remove duplication between state and federal level requirements.

Cross-sector demand management

State and territory governments have increasingly prioritised cross-sector coordination in infrastructure planning and delivery, recognising transport as a key enabler of housing, energy transition, and strategic economic precincts. Coordinator General roles in Western Australia and New South Wales exemplify this integrated approach, aligning transport investments with broader objectives in urban development, energy, and regional growth.

Western Australia

Infrastructure WA (IWA) has taken a proactive role in addressing market capacity challenges across Western Australia, with a particular focus on the Western Trade Coast (WTC) — a nationally significant industrial precinct.

In response to the WA Premier’s mandate, IWA has supported portfolio scheduling and initiated a market capacity pipeline to support coordination of infrastructure delivery across major project delivery agencies including Westport, Department of Transport and Major Infrastructure, Fremantle Port Authority and Water Corporation. This work has already identified a significant uplift in projected construction expenditure through 2028–2040 and the importance of information sharing between State and Commonwealth, including the Department of Defence, on infrastructure planning and delivery.

Building on this momentum, IWA is advancing an analytics program, in close collaboration with Infrastructure Australia, to forecast demand and supply pressures, at both at an aggregate and project-level, for labour, materials, and plant—critical to ensuring on-time, on-budget delivery.

This collaboration is already delivering tangible benefits through testing, calibration and validation of the data, and models, and demonstrates collective leadership and cooperation in infrastructure delivery coordination, data-driven planning, unlocking opportunities for innovation, workforce planning & development (including IA’s Net Zero workstream), and strategic investment across WA and the Nation.

Similarly, the New South Wales Government has strengthened cross-sector coordination for strategic infrastructure projects by expanding the Infrastructure Coordinator-General function within Infrastructure NSW (INSW).10

Since 2024, it has carried an expanded role that includes leading coordination across housing, energy, and employment-related infrastructure priorities, particularly in Western Sydney and the Aerotropolis. This includes aligning planning and delivery timeframes across agencies to reduce delays and duplication.

The Coordinator General also has powers to intervene and resolve roadblocks or disagreements between agencies, ensuring critical projects progress without unnecessary red tape.

Its immediate focus areas include:

- Infrastructure to support housing targets and reforms under the National Housing Accord.

- Coordination of enabling works for the Electricity Infrastructure Roadmap, including transmission and renewable energy projects.

- Freight and logistics infrastructure to unlock employment lands in Western Sydney.

- Aerotropolis Sector Plan: INSW sequences and prioritises transport and water infrastructure to enable development across the Aerotropolis, ensuring integrated planning for roads, utilities, and airport-related growth.

INDUSTRY VIEW SECTION 1: Understanding demand

Current capacity remains similar to last year, but delivery confidence is higher

Similar to 2024, six in 10 organisations view the current market capacity as about the same as last year (60%), one in four (26%) think it is worse, and few (9%) describe it as less challenging.

Industry reports stronger confidence in ability to deliver in the short and longer term. A majority of organisations are confident in their ability to deliver infrastructure projects over the next 12 months (67%), the next two to four years (64%) and in more than five years’ time (56%).

Confidence is notably stronger than in 2024, with one in four organisations (26%) reporting high confidence (‘highly likely’) to successfully deliver infrastructure projects over the next 12 months, double from last year’s survey results.

Industry reports slight uptick in capital activity, with many expecting growth over the next 12 months

More organisations have seen an increase in capital project activity over the last 12 months (31%) than have seen a decrease (23%), however four in 10 (44%) think this has remained about the same. This is similar to last year’s survey results (where 28% reported an increase and 42% reported capital activity had remained about the same over the last 12 months).

When looking at the year ahead, twice as many organisations anticipate an increase in project activity (40%) than expect a decrease (18%). Expectations for the next 12 months largely align with perceptions of recent activity, with the majority of organisations that experienced increased activity over the last year anticipating further growth and those who experienced no change or decreased activity largely expect a continuation of these trends.

Inconsistent pipeline of work in each state and territory predicted to constrain capacity

Over the next 12 months most organisations are concerned by capacity challenges in New South Wales (30%) and Victoria (27%) followed by Western Australia (16%) and Queensland (15%), and the smaller states and territories.

In the longer term, industry anticipates capacity opening in New South Wales and Victoria, as large civil projects progress through the delivery phase and the forward pipeline weakens. However, market capacity is expected to become more constrained in Queensland and South Australia with pipelines firming around the 2032 Brisbane Olympics and key defence projects in those regions.

Industry noted the key issues impacting capacity in specific geographic regions include:

- uncertainty about state / territory government fiscal priorities and forward pipelines, despite continued high demand for infrastructure investment in growing cities.

- delayed or ‘fluid’ start dates, longer approval waits and shorter delivery timeframes in some states, following extended procurement processes in which tenderers compete on both cost and delivery timeframes.

- competition between states to fill labour and skills shortages on large resources and construction projects pushing up costs and compounding shortages in smaller states.

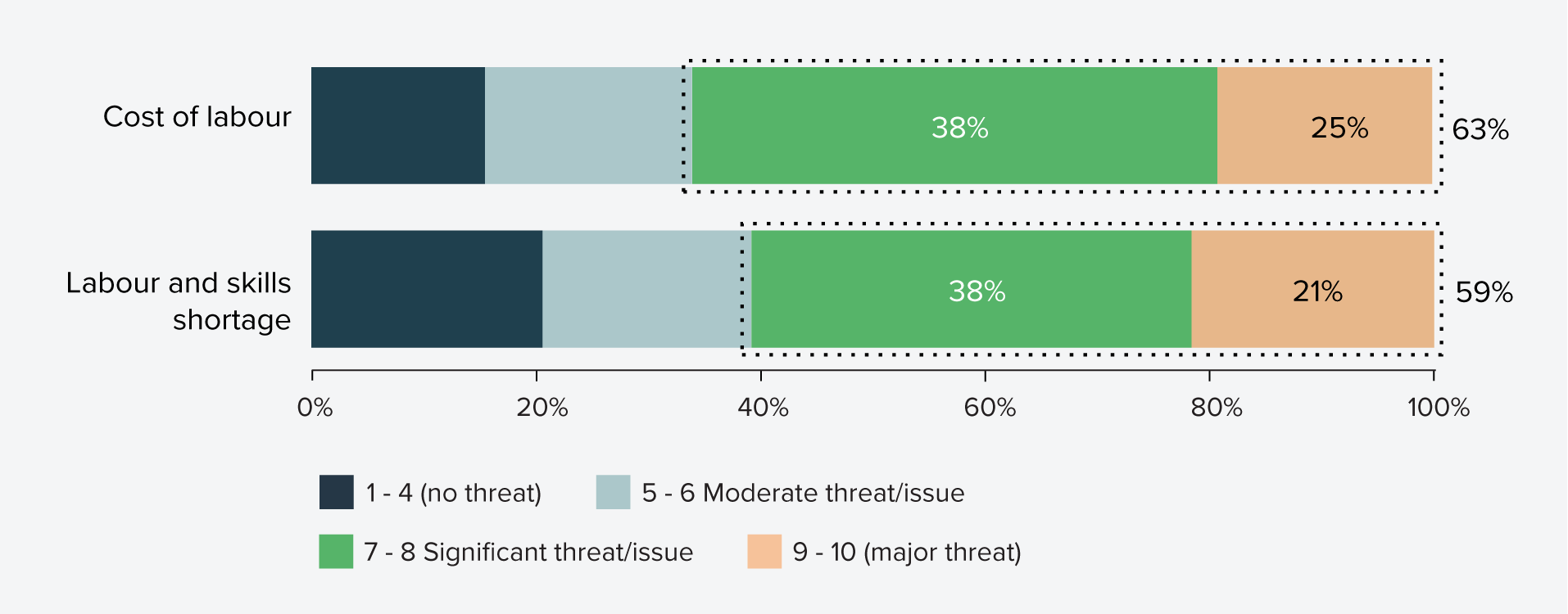

Labour and material supply disruptions remain the leading causes of project disruption

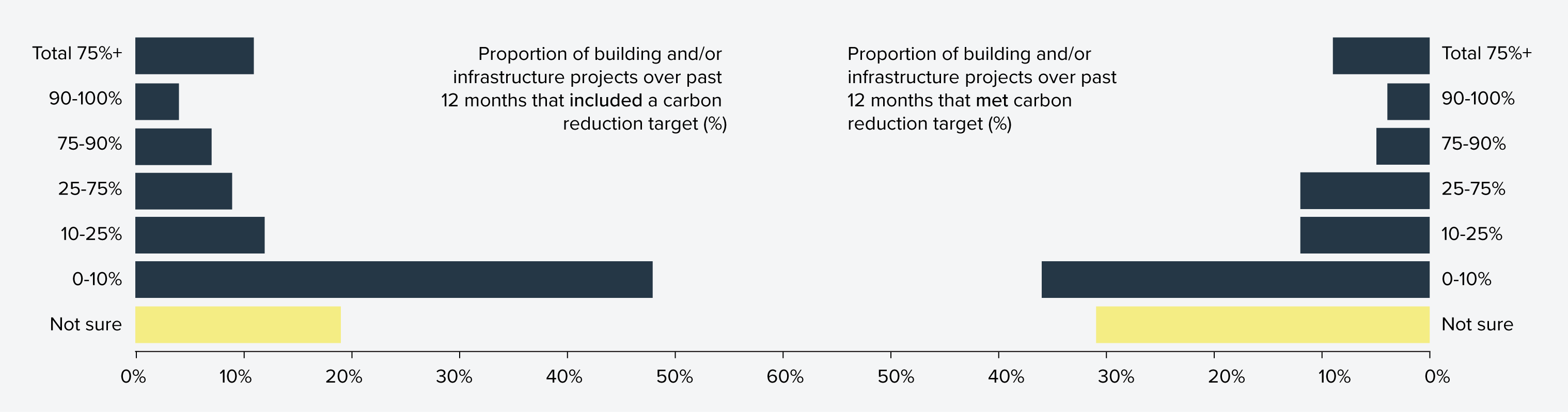

Organisations report that disruptions to project delivery are being driven primarily by cost of materials (64%), cost of labour (63%) and labour and skills shortages (59%), as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Severity of disruptions to project delivery as reported by industry (%)

SECTION 2 SUMMARY: Non-labour supply

Boost materials supply – future opportunities

2. Governments could consider measures to ensure fabricated steel products used in infrastructure projects consistently meets Australian Standards by:

- Setting standards for imported fabricated steel that meet domestic quality and safety standards, and developing a traceability and certification system to track imports, and

- Ensuring compliance with these standards on major infrastructure projects across the country.

Summary

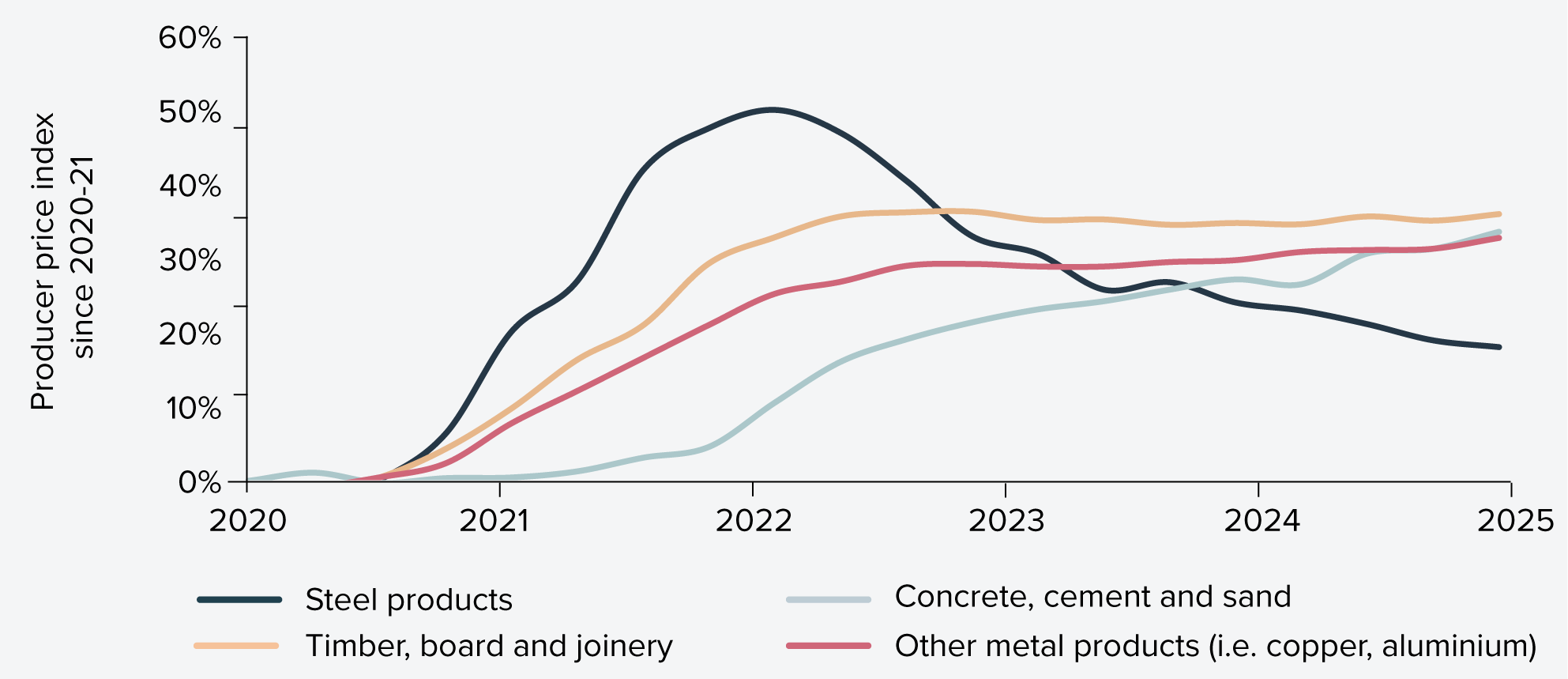

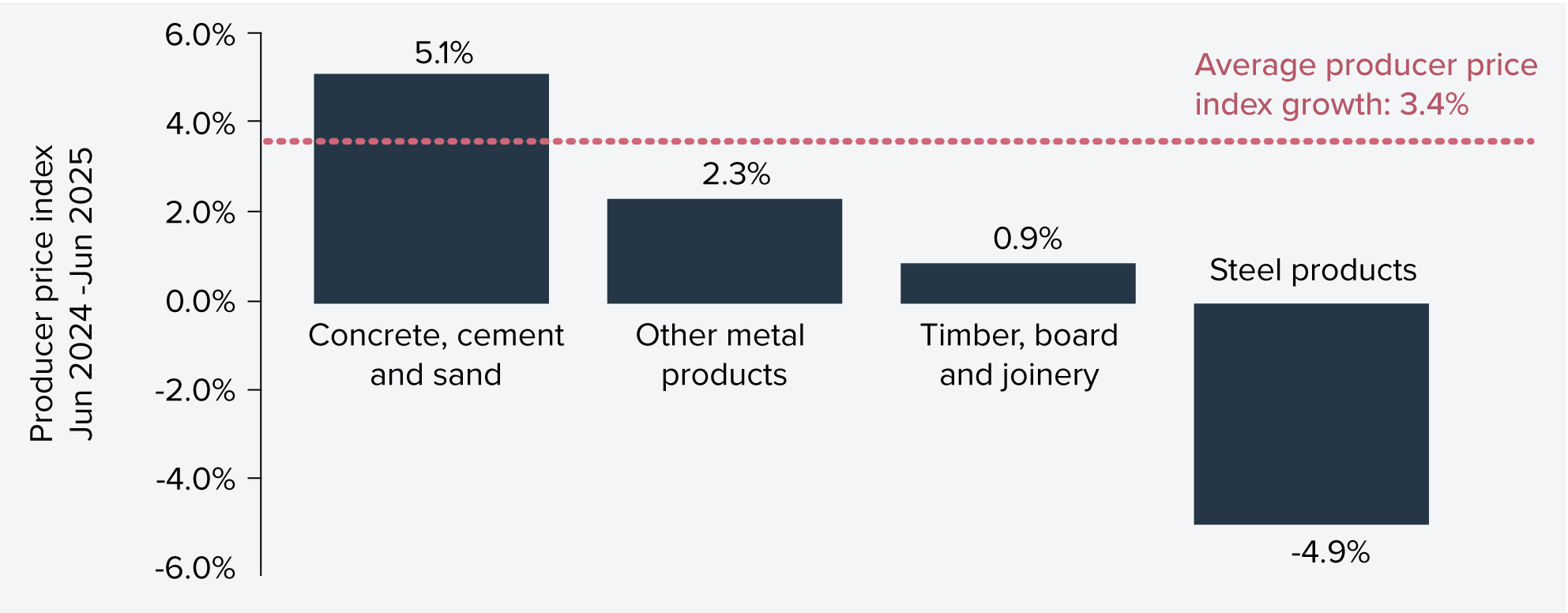

- Prices of key construction materials rose modestly in line with inflation (to June 2025), with the only exception being steel prices which fell by 4.9% over the same period, continuing a downward trend since 2022.

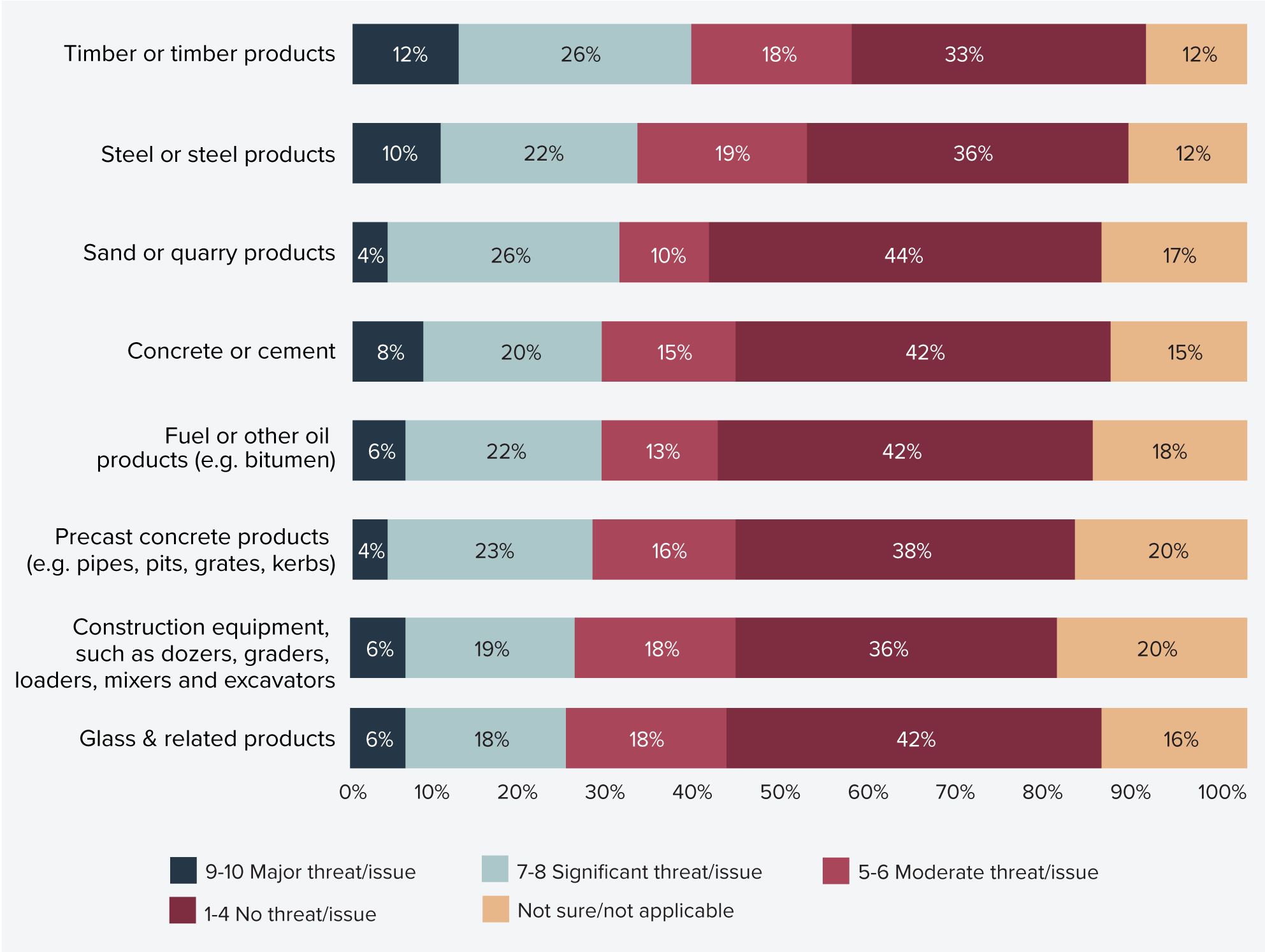

- Industry identifies steel and steel products, along with concrete and cement, as the highest-risk materials for delivering transport and utility projects — around one-third of surveyed respondents rated these as major or significant threats to successful delivery.

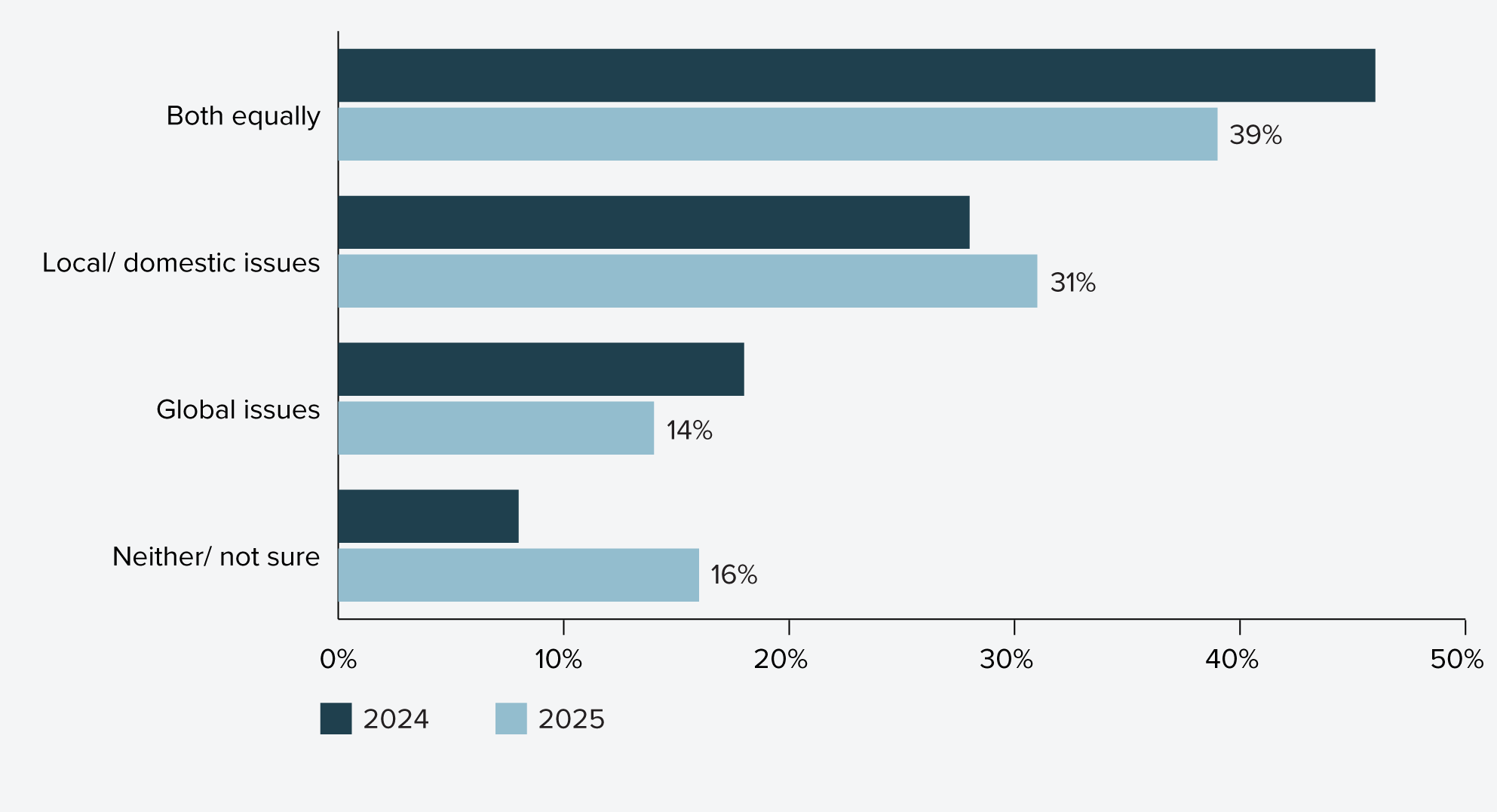

- Supply chain risks are now more balanced: 39% of organisations see domestic and international issues as equal risks, 31% view domestic issues as most problematic, and 14% global issues; only 12% rate international disruptions as a major threat (down from 16% in 2024).

- Domestic steel fabrication is critical but under pressure: the sector (42,000 jobs, $18.7 billion sales) supplies essential infrastructure components but faces rising insolvency and import competition.

- Quality concerns over imports and inconsistent enforcement of Australian Standards persist. Governments are investing in green metals and key assets for steel manufacturing capacity (e.g., Whyalla Steelworks, Port Kembla upgrades) to maintain sovereign capability. More could be done to shore up domestic fabrication capacity further down the supply chain.

- Lower emissions materials are critical for reducing embodied infrastructure emissions but are underutilised: while governments have funded initiatives and research programs to promote low-carbon and recycled alternatives, uptake remains slow due to prescriptive specifications, weak demand signals, and unclear commercialisation pathways. Stronger procurement levers, performance-based standards, and capability building would help to scale adoption and meet net zero targets.

SECTION 2: Non-labour supply

The price of key construction materials grew slightly and in line with inflation

Figure 9 shows that over the 12 months to June 2025, the price of concrete, cement and sand products rose by 5.1%, the price of timber, board and joinery products rose by 0.9% and metals (such as copper and aluminum) grew by 2.3%. This broadly aligns with the Producer Price Index’s growth of 3.4% over the last 12 months to June 2025 and reinforces a post-COVID trend where materials prices have risen higher than wages, which increased 3.2% for the construction sector in the same 12 months.

The price of steel and steel products however continues to drop

Unlike other key construction materials, the price growth of steel and steel products has dropped from a high in 2022 — a trend that has continued this year with a further 4.9% drop over the 12 months to June 2025. See Figure 9.

Figure 9: Increase in price in selected materials – past 12 months and trend since 2020-21

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2025)11

Industry report steel and concrete supply as the top risks to delivery of transport and utilities projects

Response from Infrastructure Australia’s annual Industry Confidence Survey indicates that the supply of most key materials continues to impact project delivery. Figure 10 shows that approximately one in three organisations highlighted supply of timber and timber products (38%), steel or steel products (32%) and concrete or cement (28%) as a major or significant threat to successful delivery. This reflects findings from last year’s survey, highlighting the continued importance of these supplies for successful project delivery.

Figure 10: Supply chain risk factors to successful delivery of infrastructure projects in the last 12 months (%)

Source: Infrastructure Australia Industry Confidence Survey (2025)

Drilling further down into survey responses, indicative top materials risks by sector are as follows:

- Transport projects: supply of steel or steel products pose the highest risk, followed by construction equipment and sand, then quarry products.

- Utilities projects: supply of construction equipment, followed by steel or steel products, then concrete or cement.

- Residential housing projects: supply of steel or steel products, followed by timber or timber products, then concrete or cement.

Industry expects non-labour costs to continue increasing

Six in 10 surveyed organisations observe non-labour input costs for infrastructure projects have increased over the last 12 months (68%, including 25% who have seen these ‘increase a lot’).

Almost half (48%) believe prices have been accelerating over 2025 and more than a third (36%) think prices have not yet peaked. These results are similar to last years’ findings, indicating the outlook on materials supply prices has remained steady over the last 12 months.

Supply chain risks are more subdued, and caused by both international and domestic issues

Figure 11 shows that businesses generally viewed both international and domestic supply issues as posing equal risks to project delivery, as voted by 39% of surveyed organisations. 31% of organisations believe local or domestic supply chain issues are most problematic while 14% believe global issues are more problematic. Compared to last year’s survey findings, domestic/local issues appear slightly more pronounced (31% vs 28%).

Overall, the market reports less international supply chain issues than last year. Of surveyed organisations, 14% believe international supply chain disruptions, shortages or delays are a major threat to successful project delivery, dropping from 16% in 2024.

Figure 11: Comparison of the source of supply chain issues reported in 2024 and 2025

Source: Infrastructure Australia Industry Confidence Survey (2025)

SECTION 2 SPOTLIGHT: Domestic steel fabrication capacity

Fabricated steel products are crucial inputs in construction

Steel is a critical input material needed to deliver Australia’s infrastructure pipeline. Steel fabrication is essential in construction products such as foundations, piling, columns, beams, and girders. Areas of specialisation include wind turbine towers, transmission towers, equipment for mining, armoured vehicles for Defence, naval and domestic ship building, and rolling stock.12

An estimated 26.6 million tonnes of structural steel elements is needed to deliver Australia’s construction pipeline over the five years 2024–25 to 2028–29, of which public projects on the Major Public Infrastructure Pipeline will need 3.6 million tonnes. As the estimated national steel fabrication capacity is approximately 1.4 million tonnes per annum,13 meeting this demand will require a combination of locally produced and imported steel.

The volume of imports has grown rapidly in recent years, in the face of demand and cost challenges, but quality is difficult to ascertain

Fabricated steel imports have risen sharply, with 2024 volumes nearly 50% higher than the yearly average between 2016-2021 (Australian Steel Institute, 2024). Australia’s steel fabricators claim these imports are often priced at 15-50% below domestically produced products.

It is difficult however to ascertain whether imported steel products are fabricated to the same quality and safety standards as locally made products (AS/NZS 3678, AS/NZS 5131). Lack of traceability and certification makes it difficult to track material compositions, manufacturing processes and quality control procedures, which increases the risk of using substandard products.

Within Australia, most government procurement specifications reference compliance to relevant Australian Standards (such as AS/NZS 5131 – Structural steel fabrication and erection, AS/NZS 3679 – Hot-rolled steel sections; and AS/NZS 1163 – Cold-formed structural hollow sections), however compliance is not mandated, and enforcement on infrastructure projects varies across the country.

At the federal level, Australian Government procurement rules require that for construction projects above $7.5 million, tender responses must demonstrate capability to meet Australian Standards. Agencies must make reasonable inquiries to confirm compliance.14

Ensuring equal quality requirements for both imported and locally produced steel is essential to maintain viability of local suppliers and safeguard infrastructure delivery

Australia’s structural steel fabrication sector comprises largely of small and medium size enterprises (SMEs), many of which are multi-generational family-owned businesses and employed over 42,000 people in 2022-23.15

Domestic fabricators claim they are under significant pressure from low-cost imports. A national survey by the Australian Steel Institute (2024) indicates that 80% of Australian fabricators are operating below the break-even capacity benchmark. The insolvency rate for fabricated metal product manufacturing has been growing since the winding back of Covid-19 temporary relief measures in early 2021, surpassing pre-Covid levels in 2023.16

While sourcing steel products offshore can help alleviate demand and cost pressures in construction, it is important to maintain an even playing field between imported and locally produced products. A strong local fabrication base ensures continuity for critical infrastructure projects, reduces dependency on international markets, and supports sovereign capability for sectors such as Defence and energy. It mitigates risk from potential geopolitical tensions, trade disruptions, and price volatility.

With imports rising rapidly in recent years, governments could help safeguard infrastructure delivery by requiring that all imported fabricated steel products used on major projects meet Australian quality standards. This would ensure an even playing field for domestic producers to compete with overseas suppliers.

SECTION 2 SPOTLIGHT: Lower emissions materials

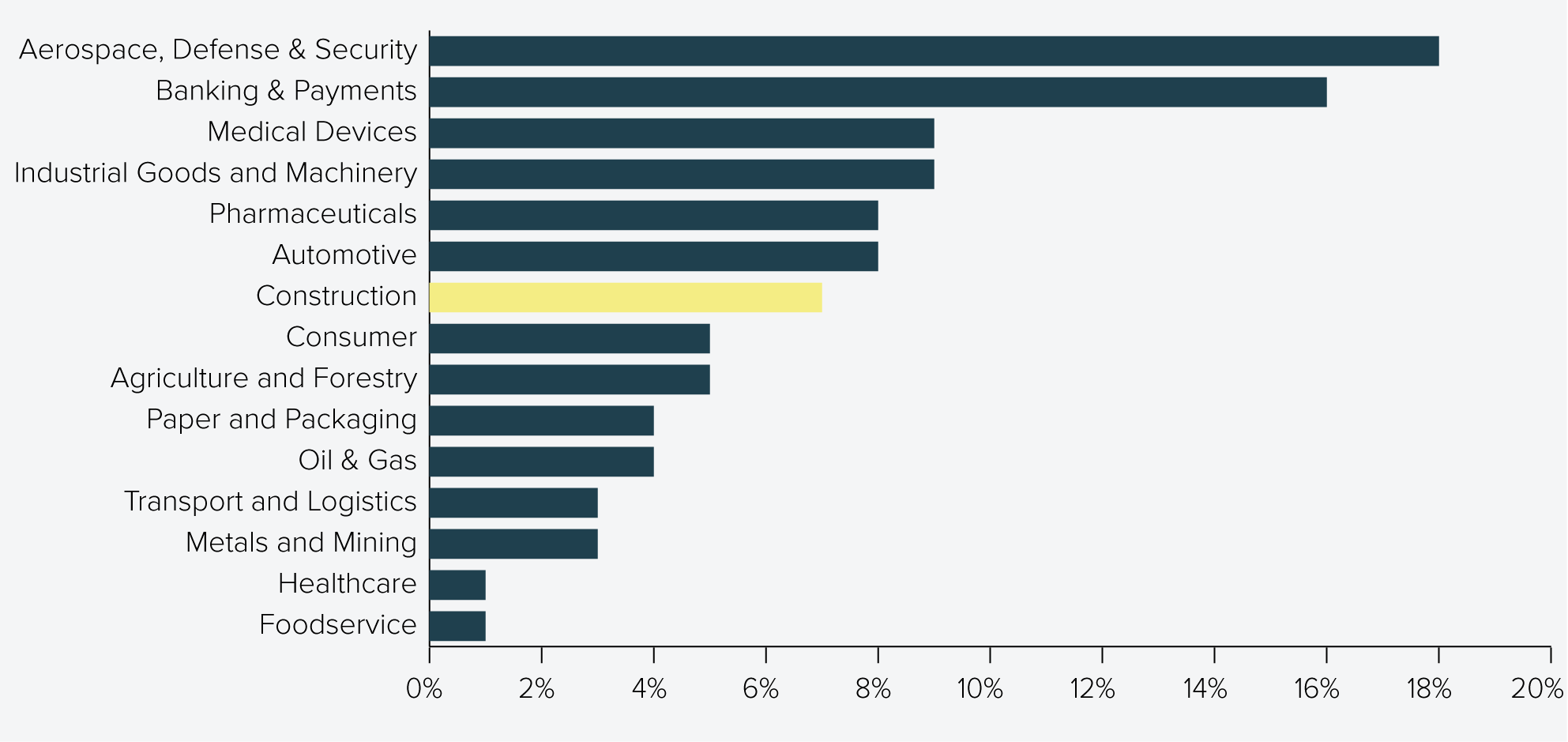

Building materials are a significant source of emissions. Infrastructure Australia’s Embodied Carbon Projections report estimates that in 2022-23, upfront embodied emissions from Australia’s buildings and infrastructure sector accounted for 7% of national emissions, with the majority arising from the manufacture of building materials.17

Promising low carbon alternatives already exist across the sector, such as concrete with lower carbon cementitious alternatives and steel products manufactured using electric arc furnace technology. Alongside these innovations, recycled materials present another pathway to emissions reduction by reducing demand for energy intensive primary processing of conventional materials, improving resource efficiency and reducing waste.

Reducing embodied emissions in transport infrastructure is an Australian Government priority, as outlined in the Transport and Infrastructure Net Zero Roadmap and Action Plan (Transport Sector Plan), released in September 2025. The Plan notes that shifting to lower emissions construction materials will not only be critical to achieving this priority but also presents a major opportunity to strengthen domestic capability and position Australian industry to compete in global markets in this space. It considers opportunities to reduce emissions through optimised design and procurement, including the use of recycled materials.

Governments have committed to using lower emissions materials

Governments recognise the opportunity to incorporate lower emissions materials in infrastructure builds. In addition to whole-of-government sustainable procurement policies, several jurisdictions have introduced infrastructure-specific policies that embed environmental and circular economy objectives directly into project planning and delivery. Examples include Victoria’s Recycled First Policy, Western Australia’s Transport Portfolio Sustainable Infrastructure Policy and New South Wales’ Decarbonising Infrastructure Delivery Policy. These policies aim to decarbonise infrastructure, drive demand for recycled and low carbon materials, and embed sustainability considerations into procurement and investment decisions.

At the federal level, all governments have committed to optimise recycled content in transport infrastructure as part of their procurement practices under the Federation Funding Agreement Schedule (FFAS) on Land Transport Infrastructure Projects. Under the FFAS, jurisdictions are required in 2025, for the first time, to report on their uptake of recycled content in infrastructure projects or establish annual reporting against recycled content uptake.18

This marks a significant first step in collecting data and setting comparable, if not consistent, baselines on the uptake of recycled content across the country.

The Australian Government has also invested in applied research initiatives such as the SmartCrete Cooperative Research Centre ($21 million over seven years from 2020) to co-fund and coordinate collaborative research to improve the durability, performance, and environmental footprint of concrete used in infrastructure.19,20

Other funding initiatives highlighted in the Australian Government’s Transport and Infrastructure Net Zero Roadmap and Action Plan include $59.1 million awarded via the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) to support low emissions steel, iron and renewable hydrogen research and development, $750 million to support green metal projects through the Future Made in Australia Innovation Fund and low or no cost loans from the Clean Energy Finance Corporation for low carbon concrete initiatives in housing and industrial developments.21

Industry faces various barriers to scaling up supply of lower emissions materials for infrastructure construction

Despite efforts by Australian, state and territory governments, the current uptake of low emissions and recycled materials remains low. Structural barriers and inconsistent demand signals continue to constrain the industry’s ability to scale production and investment.22

SmartCrete for example, has called out poor commercial adoption and uptake of research as a critical barrier to achieving its goals. It has noted that while technical solutions for low-carbon concrete exist, procurement and market practices remain the biggest impediment. The current procurement model — focused on lowest cost and short-term performance on project-to-project basis — discourages innovation and uptake of sustainable materials. This results in a “valley of death” where research outcomes fail to transition into large-scale commercial use.23

A key barrier is the persistence of prescriptive project requirements, which tend to specify material types and inputs rather than outcomes. This approach prioritises established methods and materials but often prevents the adoption of proven low-carbon alternatives. Shifting towards performance-based specifications would allow suppliers greater flexibility to innovate, while still meeting quality and safety outcomes.

Industry also reports uncertainty around the pathways from research to commercial application. Significant investment can go into development and testing new materials, only for them to be excluded by unclear or inconsistent specifications. Developing transparent and nationally consistent processes for testing, approval and commercialisation would provide certainty, reduce risk and encourage suppliers to invest more confidently in new materials.

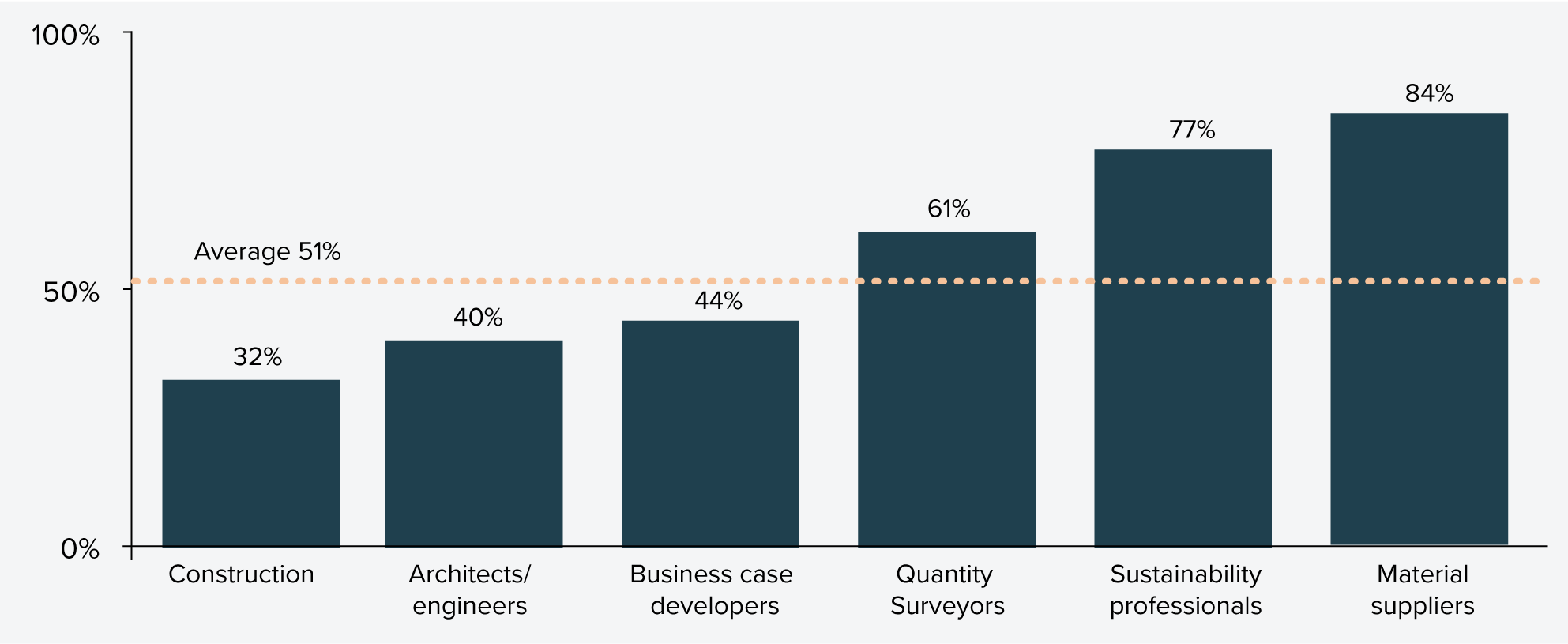

Opportunity to upskill and change culture to embrace new materials

The rapid development of various types of lower emission materials presents a challenge, but also an upskilling opportunity for industry and government proponents. On the government side, decision makers and advisors responsible for project design, procurement and market engagement might not have the most up-to-date knowledge to help them weigh up the benefits and risks of adopting low carbon materials, set the most appropriate technical specifications, or access supply availability for proposed projects.

Building capability within project teams on both sides — through training, embedding carbon expertise and providing clearer guidance on the adoption of new and emerging new low emissions materials — can ensure that materials specifications are appropriately set and that projects optimise the use of innovative materials without compromising quality or safety. The Australian Government, under Priority Action 5 of the Transport Sector Plan, is supporting decarbonisation capability in the private and public sectors. Through the Infrastructure Transport Ministers’ Meeting, it is exploring an infrastructure capability building program and a central knowledge hub, which could provide carbon literacy training, showcase low-emissions innovations and share practical resources for low-carbon solutions.24

SECTION 3 SUMMARY: Workforce and skills

Expand labour supply – future opportunities

Governments could explore opportunities to coordinate and align emerging training programs across jurisdictions to accelerate the development of priority construction workforce skills in digital technologies, modern methods of construction, and decarbonisation.

This could include sharing lessons learned, promoting standard approaches to course design delivery and facilitating cross-jurisdiction recognition of prior learning for unaccredited training to improve workforce mobility.

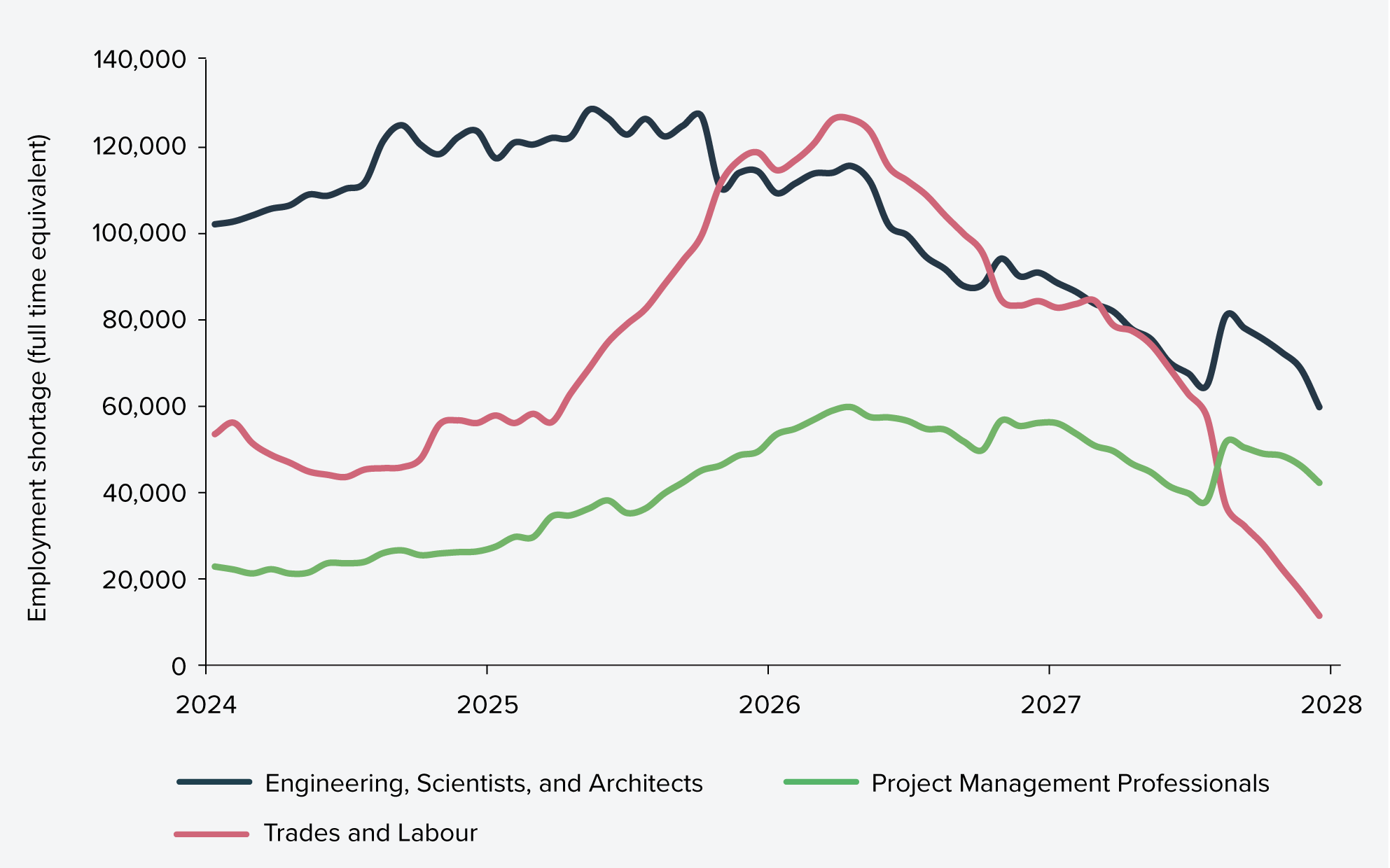

Summary

- As at October 2025, Australia’s current infrastructure workforce stands at 204,000 workers.

- There is an estimated shortage of 141,000 workers, which could reach a peak of 300,000 by 2027.

- By occupational groups, shortages for both Architects and Scientists as well as Trades Workers and Labourers will peak at approximately 126,000, with the latter rising quickly.

- Labour continues to pose a substantial delivery risk with 63% of firms surveyed this year citing labour cost and 59% citing labour and skills shortages as a substantial threat to delivery.

- Professional roles such as engineers and designers are stretched across new growth sectors – energy, water, and commercial sectors while demand for transport work keeps at pace.

- Energy infrastructure pipeline uncertainty is prompting companies to adopt a cautious ‘wait and see’ approach to workforce and skills investment. This means rather than committing to long-term training or recruitment, many are relying on redeploying workers from adjacent sectors to meet short-term demand. However, there is ambiguity on the level of actual transferability of skills between these sectors.

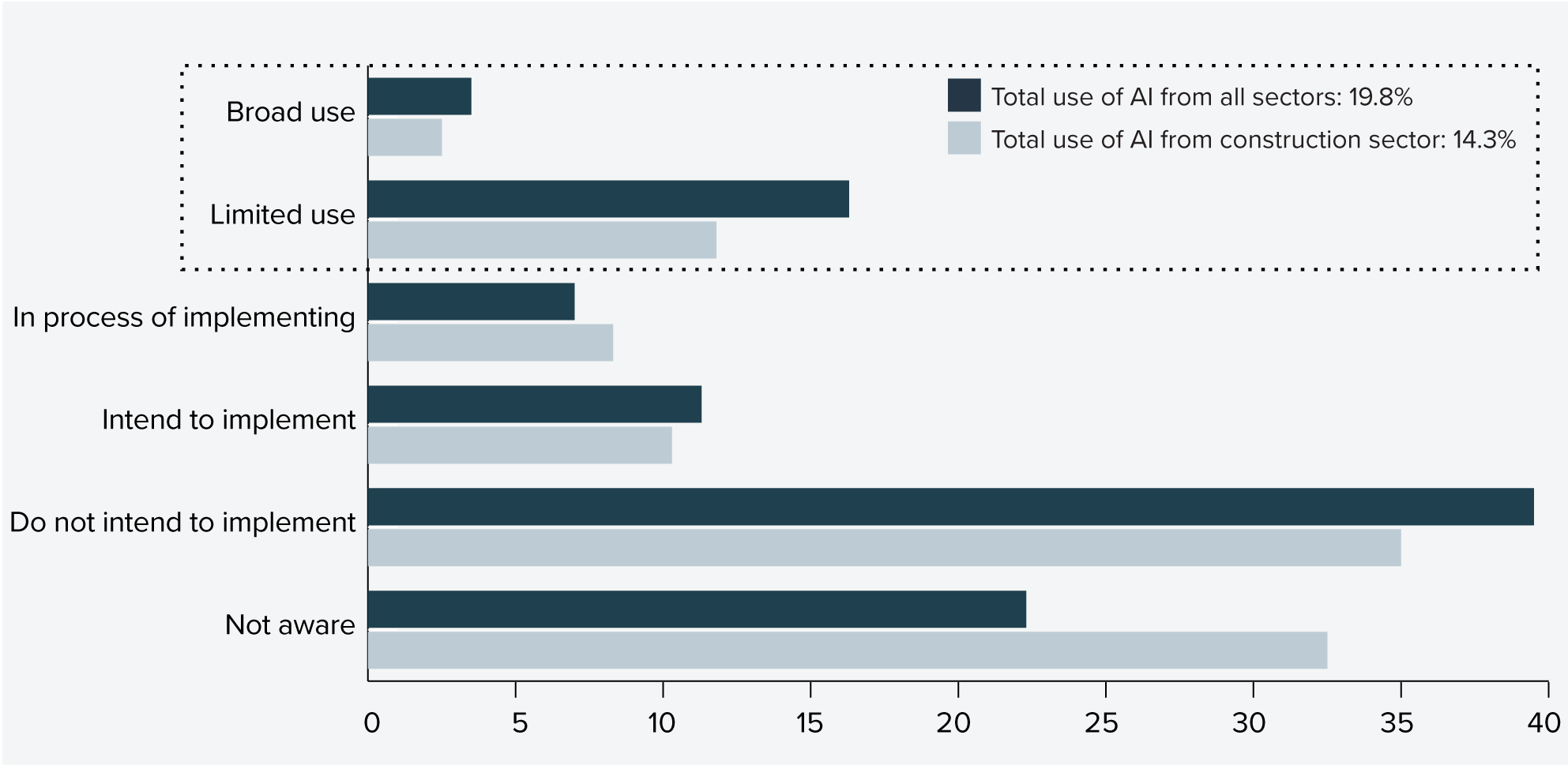

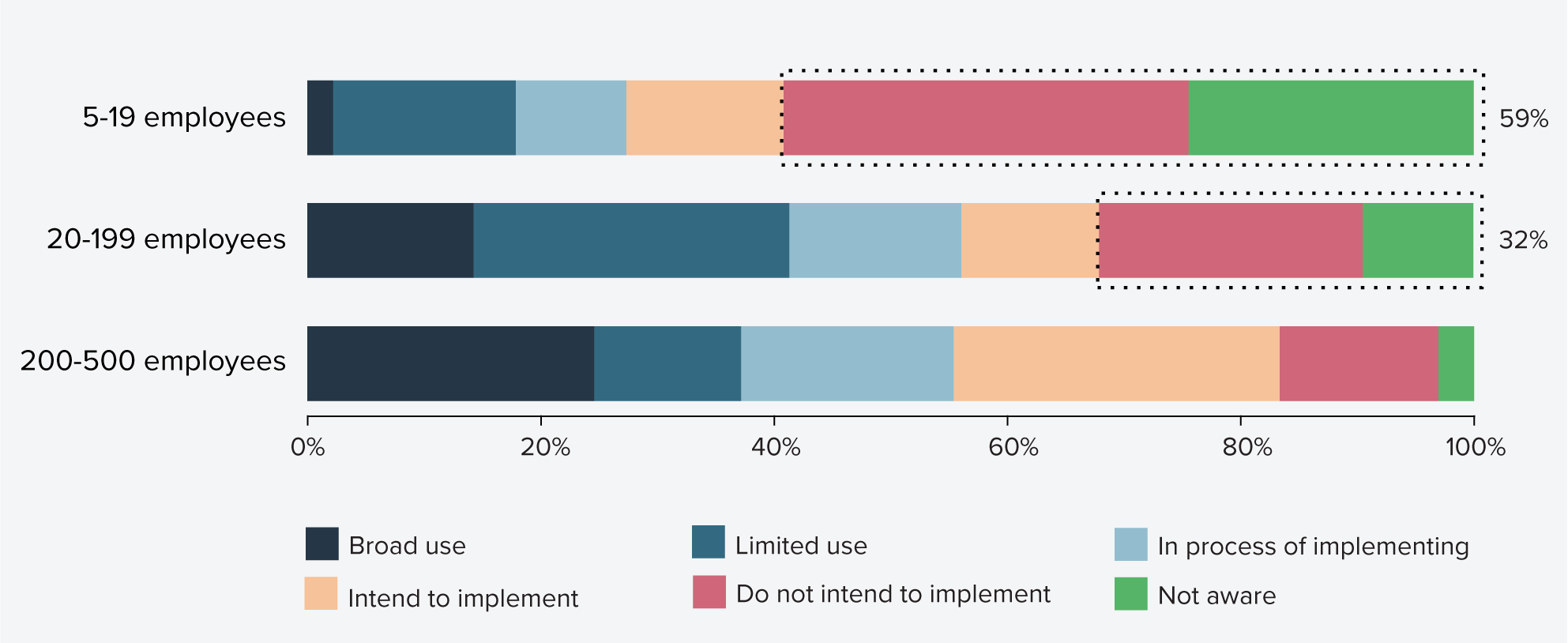

- Australia’s experience broadly reflects global trends, which show a construction workforce struggling with persistent labour shortages and at the same time being reshaped by two key drivers - rapid digitalisation and decarbonisation.

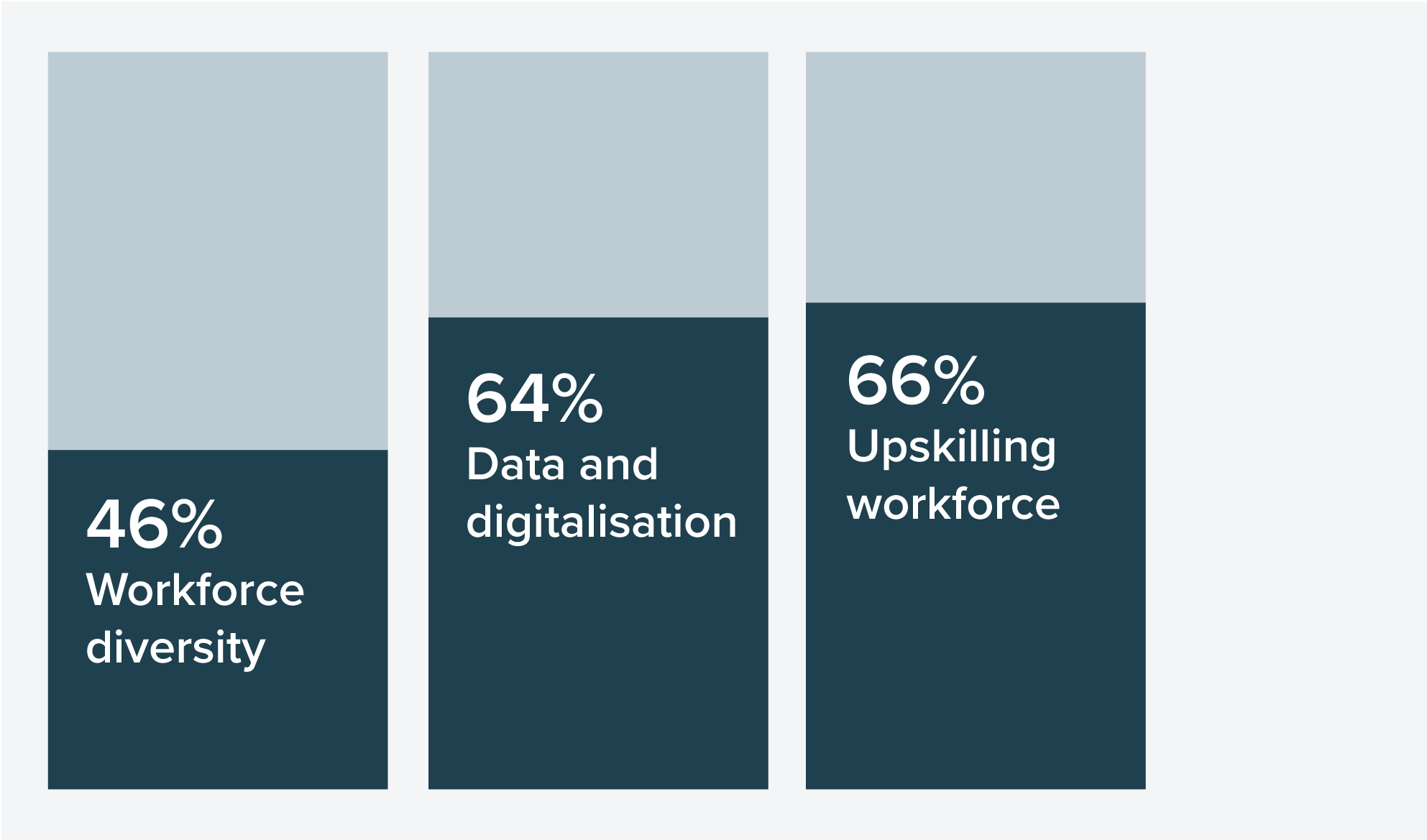

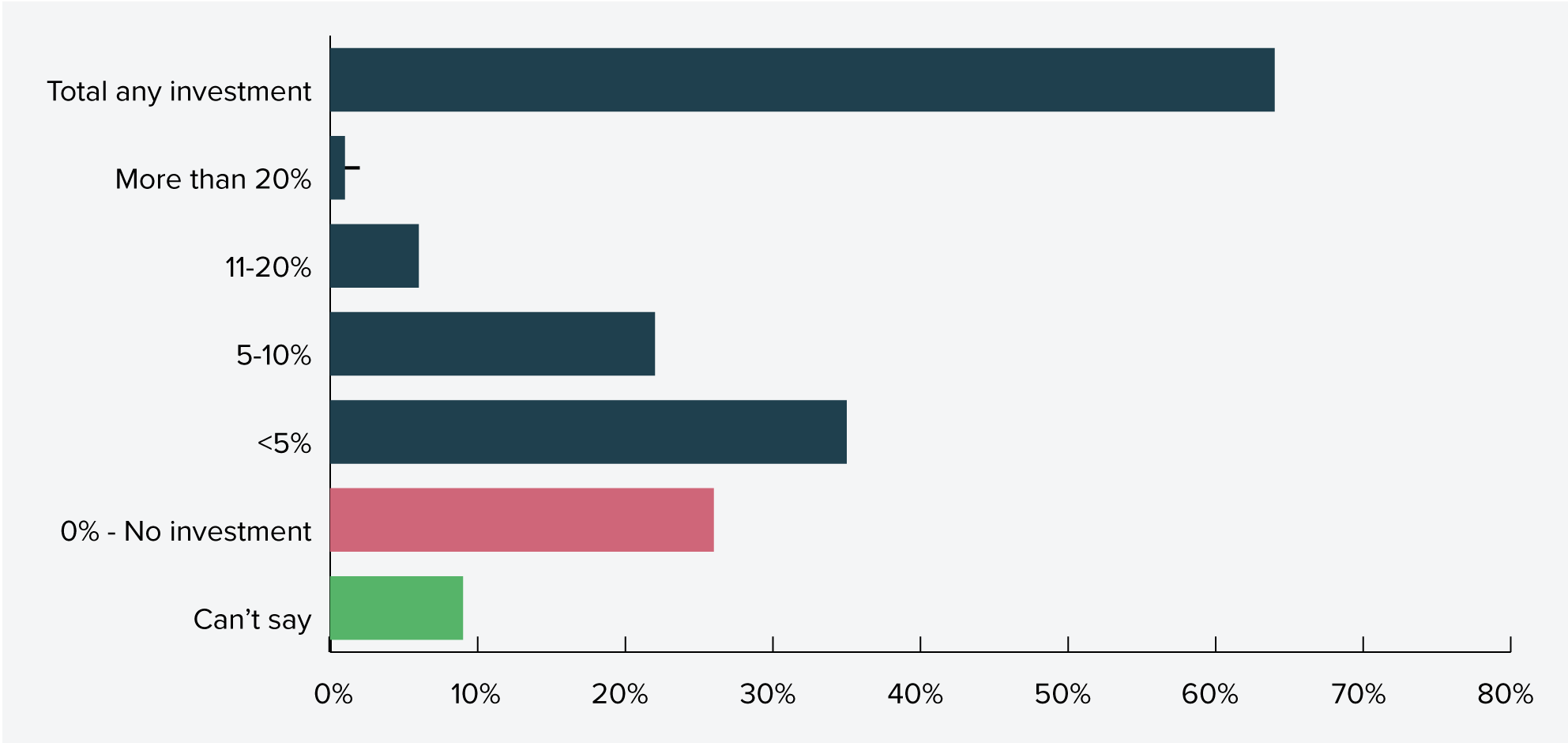

- 66% of the sector has invested in workforce upskilling in the past 12 months, with engineers and designers investing the most in upskilling (85%).

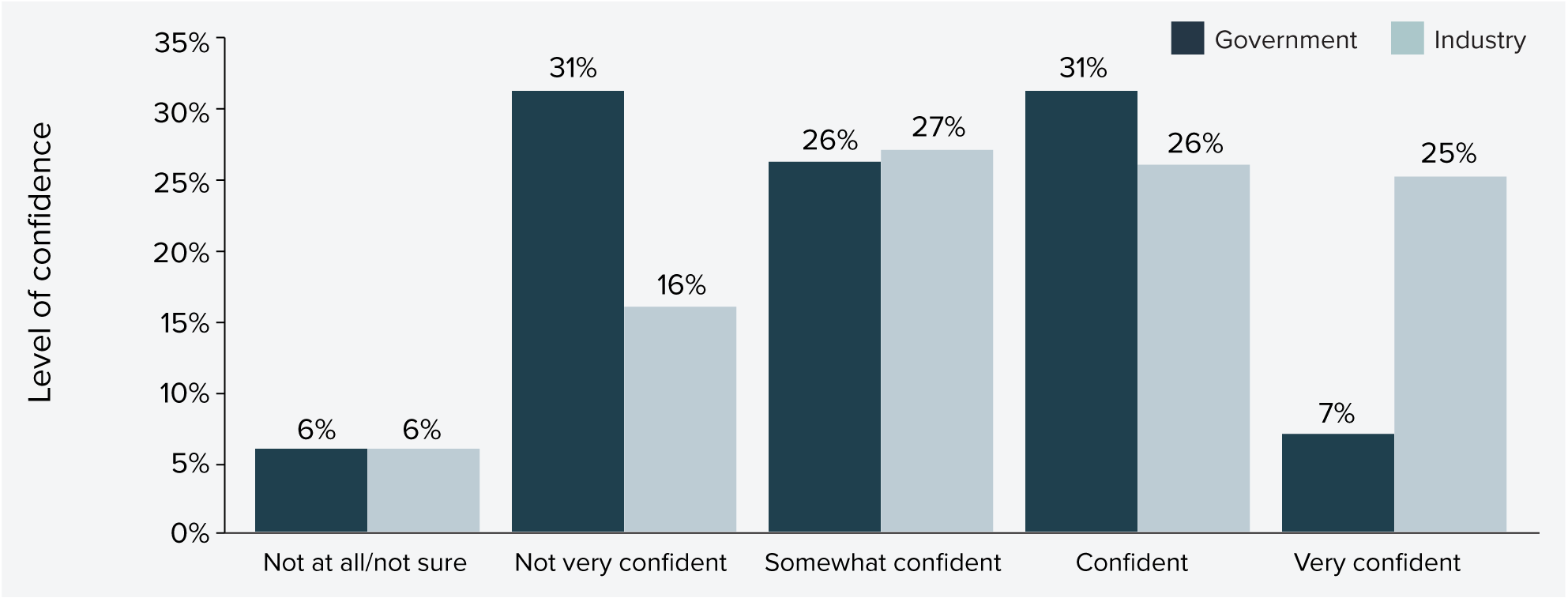

- Industry is aware of the net zero imperative, but progress is slow – one in five companies have set organisational commitments to reducing carbon.

- Low confidence and lack of guidance might explain this slow progress to embedding net zero - 40% of firms feel they lack access to emissions-reduction training.

- Industry, governments, and education and training sectors recognise and are acting on the urgent need to upskill the construction workforce. There is an opportunity to leverage lessons already learned, align and collaborate across jurisdictions to lift workforce capability in new technology and decarbonisation skills development and delivery.

SECTION 3: Infrastructure workforce supply and shortage update

The infrastructure workforce stands at 204,000, with demand growth outstripping supply

As of October 2025, there are 204,000 workers engaged in infrastructure across the nation. By occupation groups, this comprises approximately:

- 62% Trades Workers and Labourers

- 26% Engineers, Architects and Scientists

- 12% Project Management Professionals

Figure 12 shows the latest projection of demand versus supply over the five-year period. Compared to last year’s projections, peak workforce demand has increased - rising from 417,000 to 521,000 - and has shifted out one year from mid-2026 to mid-2027. This trend is consistent with observations made in previous years and is likely reflective of planned expenditure being pushed back as the market struggles to meet overly ambitious delivery targets.

Figure 12: Demand, supply and shortage of infrastructure workers (2024-25 to 2028-29)

Labour shortages could rise to 300,000 workers by 2027

We estimate a shortage of 141,000 workers on public infrastructure works as of October 2025. This is 56,000 less than was estimated in last year’s Infrastructure Market Capacity report, and reflects demand being pushed out to the later years. This reduced shortage delivers a temporary reprieve before a new shortage peak of more than 300,000 workers in mid-2027. This increased shortage of workers is going to be driven by the rise in demand for privately funded renewable energy projects, see Section 1 Understanding Demand for more information on the energy pipeline.

Figure 13 shows that shortages for Engineers, Architects and Scientists roles will peak at 126,000 in late 2026 before gradually declining over the outer years to 2028-29. Meanwhile, shortages for Trades Workers and Labourers peaks at 126,000 by mid-2027. There will be a sustained demand for Project Management Professionals, which is also projected to peak in mid-2027 at around 59,000.

Figure 13: Workforce shortage by occupational groups (2024-25 to 2028-29)

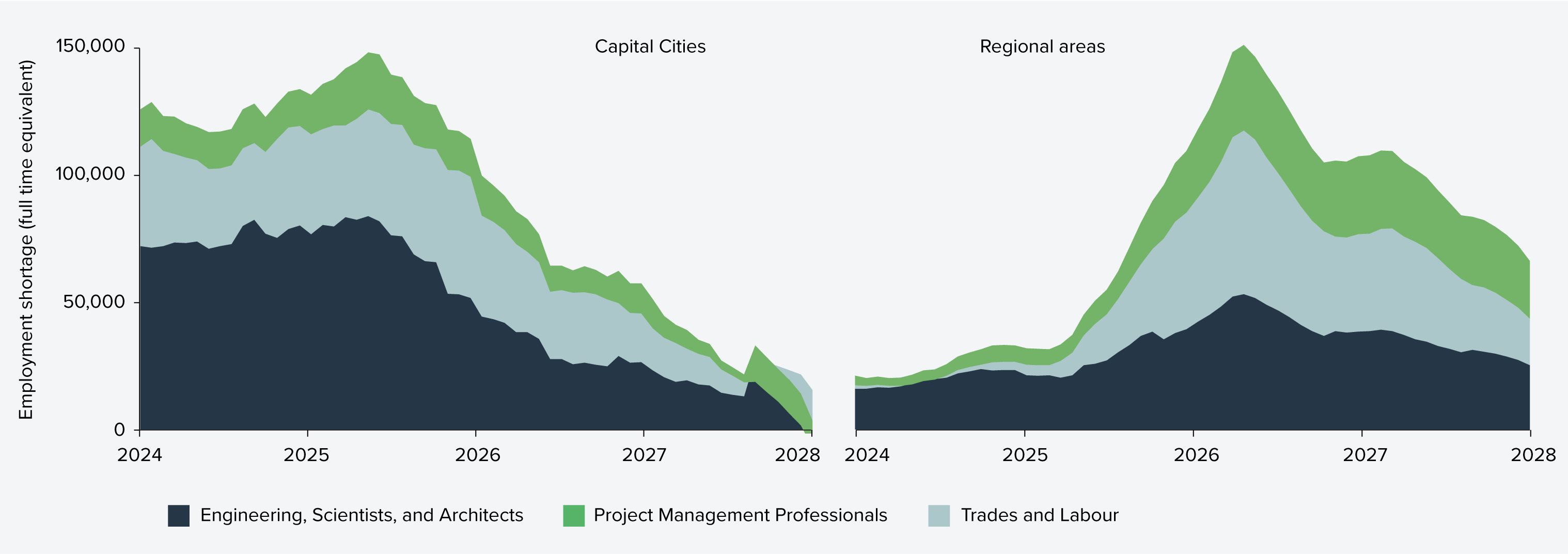

Regional shortages will increase four-fold over the next two years, driven by energy and utilities projects

Figure 14 presents a national comparison of shortages across capital cities and in regional areas (outside the Greater Capital City Statistical Areas as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Shortages in metro locations are projected to rise modestly from 131,700 in October 2025 and peak at 148,000 in 2026. Regional locations, however, will experience a much steeper increase, with the workforce shortage growing from 38,200 in October 2025 to a peak of 181,000 in 2027.

Figure 14: Workforce shortage by occupation group, capital-city areas versus regional areas (2024-25 to 2028-29)

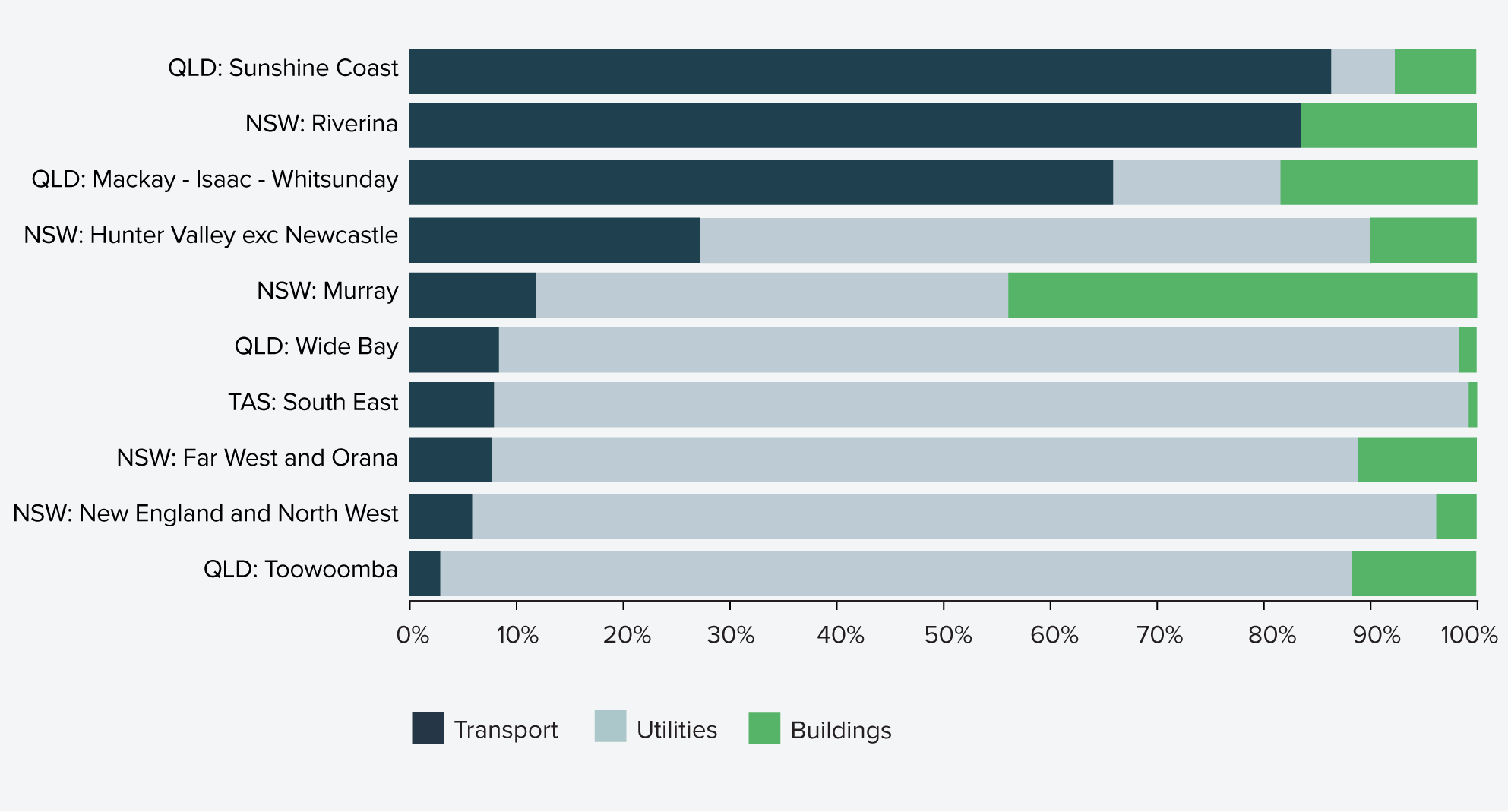

Figure 15 shows 10 hotspot regions with forecast demand over the next four years (2025-2026 to 2028-29) doubling from the demand in the four years prior (2021-2022 to 2024-24) across:

- New South Wales: New England and North West, Far West and Orana, Murray, Hunter Valley excluding Newcastle, Riverina

- Queensland: Sunshine Coast, Wide Bay, Mackay-Isaac-Whitsunday, Toowoomba

- Tasmania: South East

Figure 15: Increase in public investment from previous 4-years (2021-2022 to 2024-25) to next four years (2025-2026 to 2028-29), by region

Projected demand across the 10 regional hotspots is heavily dominated by the utilities sector, which represents approximately 60% of total demand - underscoring its significance as the driving force behind regional workforce need, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16: Projected demand breakdown by sector and region (2025-26 to 2028-29)

CASE STUDY

Filling in the knowledge gap on workforce mobility between construction sectors

BuildSkills Australia, the Jobs and Skills Council for the build environment is leading a study, supported by Jobs and Skills Australia and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, to understand and enhance worker mobility into and out of the residential construction sector.

The study focuses on core residential construction occupations - those most critical to housing delivery and most vulnerable to capacity constraints during demand surges (e.g., under the National Housing Accord target of 1.2 million homes).

Scope of the study

The study will map the actual and potential labour flows between residential, infrastructure, non-residential construction, and other sectors. It will identify:

- Where additional workers can be sourced quickly during demand peaks.

- What barriers prevent mobility (e.g., licensing, cultural differences, employment models).